The Ethical Issues Associated With Organ Transplantation Essay

Introduction, organ transplants, procurement and distribution of organs, payment for organs and transplantation surgeries, socio-economic context, effectiveness of organ transplants.

Ethics refer to them as a set of “well-founded standards of right and wrong that prescribe what humans ought to do in terms of rights, obligations, benefits to society and fairness” (Spinoza, 2006, p. 12). Law on the other hand refers to a system of rules usually enforced by a set of institutions and used to regulate the behavior of individuals in a community or a country that recognizes such rules (Spinoza, 2006, p. 13). Both ethics and law are important in guiding the behavior of medical practitioners to achieve better outcomes. This paper analyzes the ethical issues associated with organ transplantation and how such issues can be addressed within the framework of nursing ethics and law.

Organ transplantation is the act of “moving a body organ from one body to another or from a donor site in the patient’s own body, to replace the recipient’s damaged or absent organ” (Winters, 2000, p. 17). The organs that can be transplanted include the kidney, heart, eyes, and liver. Organ transplantation is one of the breakthroughs in the field of medicine. It has particularly helped in saving several lives which could have otherwise been lost due to organ failures. Despite its success, organ transplantation has been associated with serious ethical concerns which undermine its applicability. The main ethical concerns associated with it are as follows.

While organ transplantation has been widely accepted by doctors, patients, and even the law, the question of how to procure the organs legitimately and efficiently remains unaddressed. Besides, distributing the limited organs among the many patients is an ethical dilemma yet to be addressed. The methods of obtaining the organs include donations by good Samaritans, paired exchange, deceased donors, and living donors (Winters, 2000, p. 45). Obtaining organs from deceased donors remains controversial because there has never been a consensus on the definition of death (Trung & Miller, 2008, p. 323). Deceased donors are normally brain-dead (higher functions stops) even though their body organs could be kept alive through life support machines. However, some believe that brain-dead individuals are not completely dead. Thus it is not right to take their organs to benefit another patient. On the other hand, organs obtained from the body after all brain functions have stopped might not be helpful. Consequently, it will be very difficult to obtain organs from deceased donors if death is defined in terms of a situation where all brain functions have stopped. Personal beliefs in terms of convictions considered to be true and a reflection of essential values about life and death have always been used in response to this ethical dilemma. Thus the definition of death in a particular community determines the procurement of organs. In some cases, the law is used to guide the process of procuring organs (Trung, The Ethics of Organ Donation by Living Donors, 2005, p. 125). However, what is lawful might not necessarily be ethical and this further complicates the process.

The distribution of organs is also an ethical dilemma as doctors find it difficult to determine who needs the organs most. Ideally, the organs should be distributed on a first-come-first-served basis. However, fair distribution of the organs has always been difficult due to personal interests, prejudice, and ethnocentrism associated with medical practitioners (Brezina, 2009, p. 57). To ensure distributive justice, the ethical principle of beneficence and justice should be upheld. Thus there should be fairness, equality as well as relativism regarding organ distribution.

According to the ethical principle of autonomy, the patient should be allowed to decide whether to undergo organ transplantation or not. In cases whereby the patient can not communicate, the decisions on organ transplantation have always been taken by the patient’s relatives. To avoid the ethical dilemma on consent, some practitioners think that organ transplantation should be automatic unless the patient says no (Brezina, 2009, p. 65). Interest groups, however, oppose automatic transplants on the ground that it violates the patient’s constitutional right to make personal choices.

Due to the short supply of organs, money has been used to regulate their demand and supply. Some individuals sell their organs to patients while hospitals curry out organ transplants only on patients who are willing and able to pay for the service. The legality of selling organs remains controversial as some believe that it helps in increasing the supply of organs (Philips, 2004, p. 78). The sale of organs has also been opposed since it promotes organ trafficking and transplant tourism. Besides, organ trafficking puts the recipients at risk of contracting diseases since the sellers usually avoid the organ screening process. While the law rejects the sale of organs, it might be unethical to let patients die for fear of breaking the law by buying organs. According to the ethical principle of non-maleficence, the risks associated with the sale of organs can be reduced by regulating the process to benefit both the donor and the recipient of the organ (Philips, 2004, p. 79).

There has been debate on whether the limited organs should be given to individuals who contribute to their organ failures through irresponsible behavior such as alcoholism. Such individuals are normally stereotyped and discriminated against regarding organ transplantation (Kavanagh, 1991, p. 189). The ethical principle of justice, however, calls for equal treatment for all patients irrespective of their socio-economic backgrounds.

Organ transplantation is associated with the problem of organ rejection. Consequently, patients must take anti-rejection drugs for the rest of their lives to suppress their immune systems. However, this strategy makes the patients vulnerable to infections as their immune systems become suppressed (Ringos, 2011, p. 33). Responding to this ethical dilemma calls for full disclosure of the consequences of organ transplants. The doctors must tell the patients all the possible negative consequences and benefits of organ transplants. The patient should then be able to make an informed decision regarding the transplant.

The above discussion indicates that ethics and law play an important role in enhancing better outcomes in the field of medicine. They not only guide the behavior of medical practitioners but also help in making decisions that determine the future of patients. Even though organ transplantation is an accepted treatment method, its applicability is undermined by the ethical concerns surrounding it. Some of the ethical concerns associated with it include procurement and distribution of organs, consent, and paying for the organs (Brezina, 2009, p. 34). To address these ethical issues, it is important to observe the ethics and laws which govern the practice of medicine.

Brezina, C. (2009). Organ Donation: Risks, Rewards and Research. New York: Diane Publishing.

Kavanagh, K. (1991). Values and Beliefs. In C. Joan, Conceptual foundations of Professional Nursing Practice (pp. 188-192). St. Louis: Moshy Year Book.

Philips, J. (2004). Organ Transplants: How to Boost Supply and Ensure Equality. New York: Rosen Publishing Group.

Ringos, P. (2011). Organ Donation After Circulatory Death. American Journal of Nursing, 111(5) , 32-38.

Spinoza, B. (2006). The Ethics. Middlesex: Echo Library.

Trung, R. (2005). The Ethics of Organ Donation by Living Donors. New England Journal of Medicine, 9(2) , 120-130.

Trung, R., & Miller, F. (2008). The Dead Donor Rule and Organ Transplant. New England Journal of Medicine, 10(1) , 320-350.

Winters, A. (2000). Organ Transplants: the Debate Over Who, How and Why. New York: Rosen Publishing.

- Conflict Between Research and Ethics

- Evidence-Based Medicine With Patient’s Preferences

- Organ Donation: Postmortem Transplantation

- Organ Transplantation and Ethical Controversies

- Suffering of Death Organs: Organ Donors and Transplantation

- Controversies in Therapeutic Cloning

- Quality of Health Services

- Blood Transfusion Code of Ethics

- William Carlos Williams: The Use Of Force

- Compassion in Relation to Goals of Medicine and Healthcare

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2022, March 27). The Ethical Issues Associated With Organ Transplantation. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-ethical-issues-associated-with-organ-transplantation/

"The Ethical Issues Associated With Organ Transplantation." IvyPanda , 27 Mar. 2022, ivypanda.com/essays/the-ethical-issues-associated-with-organ-transplantation/.

IvyPanda . (2022) 'The Ethical Issues Associated With Organ Transplantation'. 27 March.

IvyPanda . 2022. "The Ethical Issues Associated With Organ Transplantation." March 27, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-ethical-issues-associated-with-organ-transplantation/.

1. IvyPanda . "The Ethical Issues Associated With Organ Transplantation." March 27, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-ethical-issues-associated-with-organ-transplantation/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "The Ethical Issues Associated With Organ Transplantation." March 27, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-ethical-issues-associated-with-organ-transplantation/.

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

- Commercialization of Organ Donation Words: 2814

- Organ Donation in Pakistan Words: 1217

- Organ Donation, Give the Gift of Life Words: 1423

- Human Organ Donation: Causes and Effects Words: 1800

- Organ Donation: Possibilities, Threats and Legal Issues Words: 866

- Organs Donation: Positive and Negative Sides Words: 907

- Organ Transplantation and Donation Words: 374

- The Emergence of Organ Markets: Ethical and Economic Implications Words: 3646

- Animal Transplantation and Commerce in Organs Words: 2315

- Ethics of Organ Conscription and Issues Words: 734

- Should the Sale of Human Organs Be Legalized? Words: 2107

- Tissue and Organ Transplants Words: 2039

- Ethics of Organ Allocation and Distribution Words: 682

- Ethical Considerations of Organ Conscription Policy Words: 679

- Animal Transplantation and Commerce in Organs Should Be Used to Reduce the Shortage in Organs Words: 2886

- Sale of Human Organs Should Be Legalized Words: 2081

- Alcoholics’ Rights for Organ Transplantation Words: 1539

- Organ Donation: Win-Win Agreement or a Noble Form of Cannibalism Words: 544

- Human Organs’ Illegal Sale and Trafficking Words: 1392

- Organ Sales: Analysis of the Problem Words: 1715

- Organ Trafficking Statistics, Causes, and Solutions Words: 846

- Organ Trafficking Problem and Policy Solution Words: 1682

- Individuals Should Not Be Allowed to Sell Their Body Organs Words: 1747

- The Legalization of Organ Market Words: 1101

- The Organ Trafficking Issue in Worldwide Words: 858

The Ethics of Organ Donation

The medical field has made significant advances over the years which have resulted in the development of cures for hundreds of diseases leading to lower mortality rate and higher chances of recovery from ailments for people. This has undoubtedly improved the quality and/or prolonged the lives of many patients. In the past few decades, inventions and scientific breakthroughs in the biological field have resulted in the prevalence of access to sophisticated equipment and advanced diagnostic procedures that were once only in the reins of research institutes and few specialized hospitals. Arguably one of the most novel innovations has been the use of donated organs in transplantation surgeries. The transplantation process often refers to the replacement or removal of ailing body organs. This practice has literally given patients whose dysfunctional organs would have otherwise been an irrevocable death sentence in earlier years a chance to live longer.

The fundamental reason for organ transplantation is to restore health or extend the life of the ailing patient. However, a scarcity in the number of organs available has limited access to the organs despite their high demand. In addition to this, debates mostly on moral and ethical grounds have been developed dwelling mostly on the ethical standards surrounding organ donation.

The Center for Bioethics defines an organ transplant as “a surgical operation where a failing or damaged organ in the human body is removed and replaced with a new one” (1). This kind of procedure can be undertaken on any body organ that has a specialized function such as the heart, the liver, kidneys, intestines and the pancreas. The various types of transplants may be broadly categorized as human to human and animal to human transplantations. The most prevalent form of transplantation at the present is human to human organ transplant which involves acquiring the required organ from a human being. Organs from human donors can be obtained from recently deceased people or from a living donor who are in most cases close relatives of the patient. The acute shortage of available organs has led to a situation whereby majority of the people who need organ transplants are not getting them on time or have to wait for long periods of time to get the organs. The United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) which maintains a real-time database of the status of people awaiting organs reveals that over 106,612 people are currently on the waiting list for organs in the USA. On the other hand, it is estimated that 20 patients die on a daily basis while waiting for an organ for transplantation. It is therefore evident that the current sources for getting organs are inadequate (Center for Bioethics, 14). Due to this shortage, incidences of illegal organ sale have cropped up in various parts of the world as desperate patients try to go around the long processes experienced before qualifying for an organ transplant.

Agreeably while the act of organ donation is welcomed in the medical circles as well as by the general citizenry, many controversies have developed based on how donated organs are acquired and the criteria followed during their distribution. This paper shall therefore evaluate the ethics of organ donation. Several of the arguments raised by ethicists and medical practitioners in regards to the ethical dilemmas faced in organ donation and distribution as well as their counter- arguments shall be looked at to create a better understanding on the ethics that surround organ donation. Arguably, while organ donation offers a means through which lives can be saved, ethical and human safety issues surround the practice.

Bioethics refers to the study of ethical controversies that emerge in the biological and medical realms. Over the decades, ethics and professional code of conduct have become increasingly important in pursuit for the development and sustenance of human health. According to data presented by the United Nation for Organ Sharing (UNOS), organ donations and transplantations are arguably among the most controversial topics amongst bioethicists.

Nowadays, organs can be donated from two sources. They can be obtained from living donors or from cadavers. One of the most vexing ethical debates surrounding the organ-acquisition system in the US stems mostly from the cadaveric method of organ donation. According to US laws, when a person wants to donate his organs, he must obtain a donor card. However, signing the card does not mean he is qualified to donate his organs after his death. Hansen asserts that in order to qualify as a cadaveric donor, the donors must have died from a “traffic accidents, gunshot wounds, or other circumstances that render them brain dead” (14). In other words, to qualify as a cadaveric donor, the brain of the donor must have incurred irreversible damage. After this has been confirmed, the doctors can then proceed to the organ harvesting but only after the family of the donor have consented to the organ donation. This means that the donation process can only proceed if the family acknowledges and signs off to the donation. Unfortunately, a survey presented by Goodwin indicates that, “More than 50 percent of families refuse to donate their organs” (28). Hansen attributes this refusal to the emotional trauma that follows after the death of a loved one (19). The author reiterates that this refusal stems from the general lack of adequate information about the benefits and importance of organ donation. He further asserts that due to cultural and religious differences, many people view cadaveric organ donation as a disrespectful act against the departed. This negative attitude towards organ donation has consequently led to the prevalent shortage in organs for transplantation. On the other hand, finding viable solutions for the shortage has led to many ethical controversies and disputes in the US. For example, many medical practitioners have at times been faced with the dilemma as to whether they should harvest the organs without the consent of the family members or not in order to save a life. In addition to this, others have taken this opportunity to make some extra cash on the side by selling the organs illegally to desperate individuals. Such decisions question the ethical boundaries set to govern organ donation. However, in as much as the act of harvesting organs in such situations seems unethical, lives can be saved in the process.

The distribution system of donated organs in U.S. also presents ethicists and medical critics with a chance to dispute the practice. Ethically speaking, medicine is founded under a very strong principle which is to alleviate human suffering by improving the health of the body and prolonging lives. This means that all medical practitioners have a sworn duty to preserve, respect and maintain life on an objective level. However on many occasions this does not seem to be the case. For example, getting an organ transplant in US is an expensive ordeal and the selection criterion has been rated as unfair by most of the people in the states. The multiple-listing policy which allows patients who are knowledgeable and able to travel to register and be placed on as many transplant waiting lists as possible in different regions has induced ethical debate towards the organ-allocation system. Many scholars and ethicists view this policy as unethical because only the rich can benefit from this policy while the poor wait for years in order to climb up the waiting list. However Hansen defines and supports the policy which is designed to increases patient’s mobility and gives them autonomy (13). In addition to this, the organ allocation criteria, which are suggested by the UNOS, have caused many disputes. In his book, Hansen reveals transplant centers that are responsible for getting patients in waiting lists and mentions how they successfully help the patients. He also elaborately suggests that the reason why people think UNOS’s organs allocation criteria is unfair is because they have included people with unhealthy lifestyles on organ waiting lists (15). However, one of the transplant centers, The “Barnes-Jewish Hospital” argues that society should give a chance to patients who promise to change their lifestyles.

On the other hand, finding ethical solutions to solving the organ shortage problem has also brewed some debate. Some people suggest that legalizing the organ market will lessen the shortage while others bank on animal organ transplant as the ultimate solution to the problem. The lack of adequate organs for transplantation has resulted in the increased suffering of patients and escalation of their hospital bills. Wilmut note that due to the shortage in organs caused by a lack of a market oriented means for acquiring the organs and long waiting lists, many patients have to bear with painful medical procedures such as dialysis as they await organs for an indefinite number of years (112). Some patients end up dying as they wait and the medical expenses reach an excess of $50,000 per year.

Due to the desperation that springs as a result of organ shortages, many wealthy people opt for buying the organs from the black market where priority is given to the highest bidder. In his literature, Demme reports that some of these organs found in the black market are obtained through horrible means such as drugging unwilling victims and performing involuntary nephrectromy on them to obtain the desired organs (48). Reports of the illegal organ traders not paying the donors as promised are also rife thus highlighting the lack of ethics and injustices that exist in an illegitimate and unregulated market. Creating a legitimate framework for commerce in organs would lead to a condition whereby the donors would be paid their dues and the regulated environment would ensure that cases of involuntary nephrectromy would be greatly reduced. The cost per organ would also be greatly reduced since its inflated cost is mostly as a result of the monopoly that illegal traders hold in the market. Consequently the establishment of a legal market for organ donors would suffice in the abolishment of the unethical practices used in obtaining these organs in the black markets.

In a bid to find a lasting solution, other people have suggested transplanting animal organs into humans and cloning human organs as a means to tackle the organ shortage problem in the future. Some of the basis under which animal organs have been objected against is rumored to evolve around the problem with organ rejection and infections which make transplantation of the same a risky procedure. However, Wilnut asserts that new generations of immunosuppressive drugs as well as improved medical procedures have made it possible for transplants to be accepted by the body with increased safety for the patient (56). This means that the traditional restriction of organ donations to be primarily from close relatives for compatibility issues has been removed by these new drugs. With the waiting list growing by the day and the current reliance on human donations not meeting the needs, turning to animal organs presents a viable solution which would lead to increased availability hence shortened waiting time for patients.

In addition to this, more research is underway which aims at producing animals (clones) whose blood groups and organs are genetically engineered to survive or be accepted by the human body. Upon the success of such innovative venture, the issue of compatibility will be resolved as well as that of the organ supply shortage that is evident globally from the long waiting lists in different areas. On the same note, cloned or genetically engineered animals have been known to breed faster (2 to 3 years) and will therefore produce harvestable organs at a much faster rate than humans thereby catering for the organ deficit. Noticeably, being mammals, the difference between the human and most animal organs is slight and if the aim of such transplantations is to preserve and save lives then it is a cause worth taking.

Since there are not enough organs for everyone who needs it, the right and moral way to distribute organs has been widely discussed. Some people may think organs should be distributed according to medical needs, personal merits or social contribution. Wilmut suggests that the distribution of these scarce organs should be based according to “a potential recipient’s blood and tissue types, immune-system status, length of time spent on the waiting list, and medical urgency” (52). The criteria suggested by the author seem to be ethical and fairer.

However, some critics as well as ethicists claim the UNOS suggested organ allocation criteria are unfair because they includes people on the organ waiting list with unhealthy lifestyles, like tobacco smokers, alcoholics and aged members of the society(70years and above). They claim that these types of patients should not have an equal opportunity to receive the organs as opposed to patients who take care of their health properly. Hansen asserts that since the transplant centers are responsible for placing patients on the waiting list for donated organs, “the decisions of putting alcoholics, smokers and other people with unhealthy lifestyles on organ waiting lists are made by individual transplant centers, not the UNOS” (8).

In 1984, the National Organ Transplant Act illegalized the market of human organs. Some of the grounds on which the ban on organ sales was made were on the arguments against profiteering from such business. Goodwin, one of the adherent proponents for legitimizing organ sales explains that this is an irrelevant argument all the other parties involved in the transplantation process (physicians, hospitals and recipients) profit in some manner from the transplantation (145). As such, it is only the altruistic donor who does not reap any tangible benefit from the transplant. It would therefore be justifiable for the organ donor to be monetarily compensated for their organs since some of the other parties involved, most notably the surgeons and hospital also make financial gains from this endeavor. It is therefore unethical to dictate that the donor makes no gain from his organ while not imposing the same on the other parties in the process.

As such, opening up the organ harvest market is one of the solutions suggested to solve the organ shortage problem. However, this has stirred up a large number of complaints and debates in the U.S. while some people believe that legalizing the organ harvest market benefits society and can solve the organ shortage problem in the U.S, others feels that opening up organ market is unethical and immoral. Kaserman and Barnett reiterate that if there is a market for organs, the organ donation rate will increase significantly because of economic incentives (124). In addition to this, the authors refer to the September 11 terrorist attacks as an example to point out that it is wrong for people to think opening up organ marketing is unethical. He says that “more than twice the number killed in September 11 terrorist attacks died due to a shortage in organs available for transplantation” (127). It is completely unethical to let so many people die every year simply because some people think it is wrong to donate their organs or pay organ donors.

Despite the various arguments presented in favor of commercialization, there exist some real threats to legalizing human organ sales. A particular fear is that this trade would invariably lead to the poor especially of the third world countries being preyed upon by the rich from developed countries. This is a well founded fear and an unethical move considering the fact that majority of the buyers in black markets are rich people from developed nations Chopra document how poverty combined with the allure of easy money make a poor man from Brazil sell one of his kidneys to a rich Israeli (8). This is a classic case of how the desperation of the poor can be exploited should this trade be legalized. Despite arguments that the selling of body parts leads to the donors faring better as a result of the money earned, research demonstrates that the sale of organs does not alleviate poverty as proponents for the same insinuate. A study by Goyal et at shows that in India “87% of those who sold a kidney reported deterioration in their health status… and of those who sold a kidney to pay off debts, 74% still had debts 6 years later (1591)” In such scenarios, paternalism (which in this case involves the government coming in to protect the poor people from themselves) may not only be necessary but actually preferred.

Also, while there are valid reasons for blocking the introduction of trade in organs, we must not fail to consider that without a legitimate market for organs, the black market continues to flourish mostly at the expense of the donors who do not receive nearly adequate compensation for their organs. In addition to this, the current organ shortages have led to human rights crises in countries like China where organs from executed criminals are harvested and sold off. In a rather shocking twist, this unethical behavior continues to thrive despite the widespread condemnation of the practice by human rights groups all over the world.

Furthermore, as has been demonstrated in this paper, the reliance on altruism has resulted in untold suffering and death of patients as they wait for organs to become available. This is unethical and goes against the very principle on which medicine is founded, that is to alleviate human suffering by improving the health of the body and prolonging lives. It is therefore the ethical and moral obligation of medical professions and the society at large to seek out any feasible ways though which the unnecessary suffering and death of the patients can be alleviated. The use of animal organs and the legitimization of organ commerce present the best means through which a lasting solution can be found.

Ideas such as the cloning of human organs should therefore be enacted in order to supplement the number of organs available for use. To support this statement, Wilmut suggests that cloning only part of the human body is ethical. He suggests cloning parts of the human body can indeed supplement on the organ shortage experienced globally (536). Although there are still lots of obstacles and criticism in transplanting animal organs into human and cloning human organs, in the near future when technology is improved, these two solutions may be broadly used to increase the availability of human organs and solve the shortage problem.

Organ donation induces various ethical controversies in US. One of the widely concerned controversies about it is the equality of the organ-allocation system in the U.S. The other controversy is solving the organ shortage problem. This can be countered through the legal buying and selling of organs in an established market. This paper set out to explore the ethical standards that evolve around organ donation in the United States. The various arguments developed by different scholars and ethicists have been discussed. Recommendations such as the approval of xenotransplantation as well as legalizing commerce in organs donation have been suggested as means through which the shortage in organs can be tackled. In additional to this, the ethical boundaries surrounding these methods have been discussed and possible remedies made. The animal to human transplantation has pulled in a lot of ethical controversies over the decades and as discovered, the risks prevail over the potential benefits that can be accrued from this method. On the other hand, the advantages to be gained by commercializing organs for transportation far outweigh the perceivable risks. As such, commercialization of this area will not only improve the ethics that govern the practice but also offer a solution to a problem that is claiming more lives on a daily basis. However, care should be taken to ensure that this trade is not exploited by unscrupulous person for their own benefits at the cost of the organ donors and recipients who should be the beneficiaries of these new measures.

Works Cited

Center for Bioethics. Ethics of Organ Transplantation . Center for Bioethics, 2004. Web.

Chopra, Aunj. “Harvesting Kidneys From the Poor for Rich Patients.” US News and World Report. 2008. Web.

Demme, Richard. “Ethical Concerns About an Organ Market.” Journal of The National Medical Association. 102 (2010): 46-50. Web.

Goodwin, Michelle. Black Market: The Supply and Demand of Body Parts . New York: Cambridge University Press, 2006. Print

Hansen, Brian. “Organ Shortage.” CQ Researcher . 13 (2003): 153-176. Web.

Kaserman, David and Barnett, Hubbard. The U.S. organ procurement system: a prescription for reform . USA: American Enterprise Institute, 2002. Print.

Wilmut, Ian. Perspectives on Contemporary Issues: Reading Across the Disciplines. Boston: Wadsworth, 2008. Print.

Cite this paper

- Chicago (N-B)

- Chicago (A-D)

StudyCorgi. (2022, April 12). The Ethics of Organ Donation. https://studycorgi.com/the-ethics-of-organ-donation/

"The Ethics of Organ Donation." StudyCorgi , 12 Apr. 2022, studycorgi.com/the-ethics-of-organ-donation/.

StudyCorgi . (2022) 'The Ethics of Organ Donation'. 12 April.

1. StudyCorgi . "The Ethics of Organ Donation." April 12, 2022. https://studycorgi.com/the-ethics-of-organ-donation/.

Bibliography

StudyCorgi . "The Ethics of Organ Donation." April 12, 2022. https://studycorgi.com/the-ethics-of-organ-donation/.

StudyCorgi . 2022. "The Ethics of Organ Donation." April 12, 2022. https://studycorgi.com/the-ethics-of-organ-donation/.

This paper, “The Ethics of Organ Donation”, was written and voluntary submitted to our free essay database by a straight-A student. Please ensure you properly reference the paper if you're using it to write your assignment.

Before publication, the StudyCorgi editorial team proofread and checked the paper to make sure it meets the highest standards in terms of grammar, punctuation, style, fact accuracy, copyright issues, and inclusive language. Last updated: April 12, 2022 .

If you are the author of this paper and no longer wish to have it published on StudyCorgi, request the removal . Please use the “ Donate your paper ” form to submit an essay.

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Ethical analysis of living organ donation

Benita j walton-moss , dns, aprn, bc, laura taylor , rn, ms, marie t nolan , rn, dnsc.

- Author information

- Copyright and License information

To purchase electronic or print reprints, contact: The InnoVision Group, 101 Columbia, Aliso Viejo, CA 92656, Phone (800) 809-2273 (ext 532) or (949) 448-7370 (ext 532), Fax (949) 362-2049, [email protected]

In 2003, the first 3-way living kidney donor-swap was performed at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, Md. Three new donor protocols including paired donation now allow unrelated individuals to serve as donors. Some ethicists have suggested that emotionally unrelated individuals not be permitted to donate because they will not experience the same satisfaction that a family member who is a donor experiences. Others who frame living donation as an autonomous choice do not see emotionally unrelated or even nondirected donation as ethically problematic. This article uses an ethical framework of principlism to examine living donation. Principles salient to living donation include autonomy, beneficence, and nonmaleficence. The following criteria are used to evaluate autonomous decision making by living donors, including choices made (1) with understanding, (2) without influence that controls and determines their action, and (3) with intentionality. Empirical work in these areas is encouraged to inform the ethical analysis of the new living donor protocols.

On August 2, 2003, Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions held a press conference featuring 6 persons involved in a 3-way living kidney donor-exchange. 1 Although paired donor exchanges have been reported at other hospitals, this was the first in the nation that involved 3 sets of donor-recipient pairs at 1 time.

The emergence of paired donation and other new living organ donor protocols that allow individuals unrelated to the recipient to donate encourages a call for renewed examination of the ethics of living organ donation. There are multiple ethical frameworks for examining living donation. For example, Ross and colleagues 2 used a deontological ethical approach that focuses on the duty or moral obligation of the donor to the recipient. Our article employs an ethical framework of principlism to examine living donation. Those principles salient to living donation reviewed include autonomy, beneficence, and nonmaleficence. After a brief review of the 3 types of living donation, an analysis of autonomy and the criteria of Beauchamp and Childress 3 for evaluating autonomous choice are provided. Their criteria essential for persons to make an autonomous choice include acting (1) with understanding, (2) without influence that controls and determines their action, and (3) with intentionality. The concept of autonomous choice is relevant to this discussion because without it living donation would not be ethically permissible. Living donation in this discussion refers to the donation of solid organs. The authors conclude by challenging transplant professionals to study donor decision making and the outcomes associated with the new donor protocols in order to further inform the ethical analysis of these procedures.

In 2003, 6822 individuals were living organ doors, comprising a little more than half (51.37%) of all organ donations for that year. 4 The vast majority of persons donated kidneys, and most of the remaining donated liver segments. In the broadest sense, living donation can be categorized as related and unrelated. Related donors include those who are biologically and/or emotionally related, whereas unrelated includes all others without a prior emotional or biological relationship to the recipient. Overall, there are 6 types of living donations: (1) biological, (2) emotionally related, (3) formerly incompatible, (4) paired exchange, (5) nondirected, and (6) paid donations. Biological donations occur between 2 genetically related individuals such as parent and child. Emotionally related donations occur between 2 individuals with a strong psychological connection with each other, for example, husband and wife. Formerly incompatible donations are those in which donors who are incompatible by tissue or blood type with the recipient are able to donate through a new protocol termed plasmapheresis. The blood elements that render the donor-recipient pair incompatible are removed through apheresis.

Paired exchange donations involve at least 2 donor-recipient pairs whose tissue or blood types are incompatible. The 2 recipients trade donors so that they are paired with a compatible donor. Individuals who donate using this method may be related or unrelated to the recipient. All of the previously mentioned types of donation are directed, that is, the donor is seeking to benefit a selected recipient. In nondirected donation, however, the organ is not directed to a specific individual. Instead, the donor anonymously gives an organ to an unknown recipient. Because the recipient usually remains unknown to the donor, there is no potential to benefit from observing the improved health of the recipient. Although other countries allow the payment of living donors, United States law prohibits this to avoid coercion of donors.

With the continuing shortage of organs from deceased donors, and the improved survival and quality of life observed with living organ donation, some institutions are viewing living donation as the preferred approach. Though once considered an option only if the recipient had a life-preserving need and an organ from a deceased donor was unavailable, living donation now permits advanced planning of the procedure, ideally before the need for the organ becomes critical. Although organ donation is of undeniable benefit to the recipient, the question remains: If related donors observe the improvement of health of their recipient and benefit, how do donors who are unrelated both genetically and emotionally to the recipient benefit?

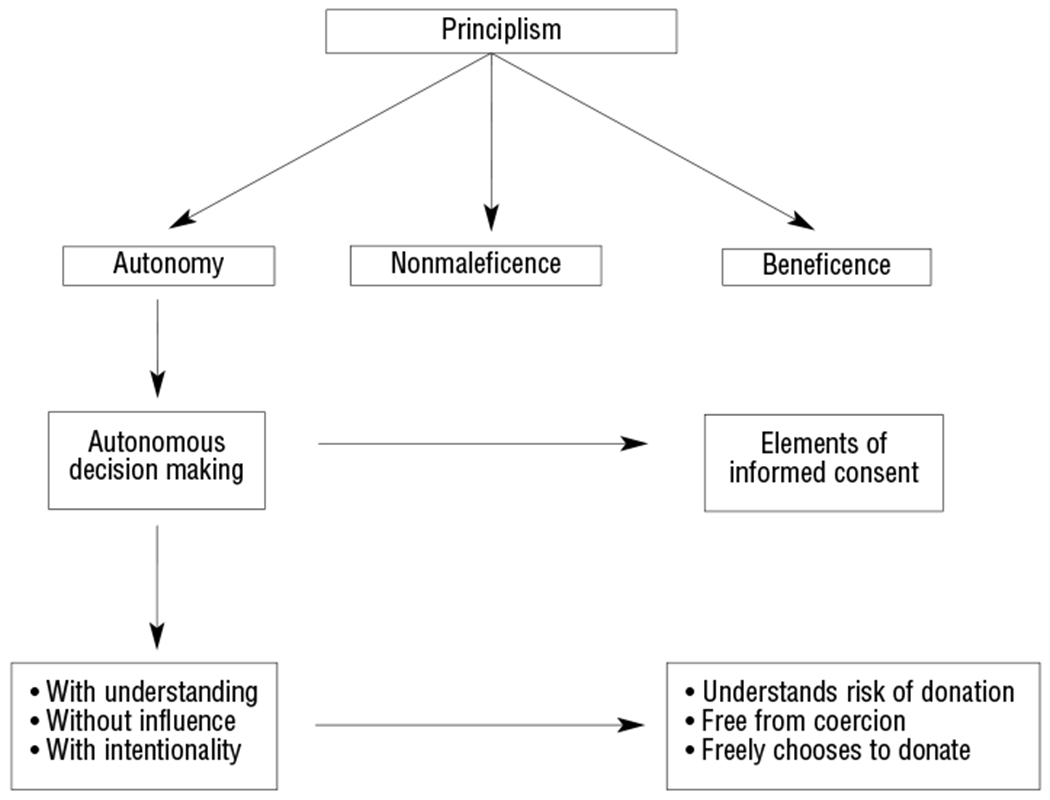

Principlism is an ethical framework that has been used to justify decision making for living donation. 5 Beauchamp and Childress 3 note that autonomy is a major component of principlism. Ethical principles, the basis of this framework, are presumed to define a “common morality.” 3 Although principlism can justify living donation decision making, it can be argued that this framework does not guide action because it is not possible to use either ethical theory or rules directly to decide a given case. 6 Further, it can be argued that for living donation, the ethical principles (eg, autonomy) discussed below are in conflict with each other. Devettere 7 explains that these principles are “prima facie,” meaning that should the principles conflict, it is then necessary to determine which principle predominates in a particular situation. Key concepts of principlism are illustrated in the Figure .

Key concepts of principlism and informed consent in living donation.

Discussion surrounding ethical justification of living organ donation is usually based on the assumption that the donor is an autonomous person. 8 Autonomy, expressed as self-determination, is the principle of self-governance 9 ; that is, persons who have the capacity to act intentionally, with understanding, should make decisions without controlling influences that would interfere with their free and voluntary actions. Albert 10 adds that respect for autonomy recognizes that individuals know what is best for themselves.

Beauchamp and Childress 3 extend Albert’s 10 notion of freedom as part of the broad definition of autonomy. Autonomy has 2 conditions: First, the individual must be free from controlling interference by others. From this perspective, the decision to donate must be respected, regardless of whether the donor will benefit personally from the act of donation. Second, the individual must be free from personal limitations that prevent meaningful choice, such as inadequate understanding. Therefore, a small child or a severely cognitively impaired person who does not have the capacity to act intentionally with understanding should not be permitted to donate. This emphasis on personal autonomy is a view more often identified with Western than Eastern culture. Because the independence and freedom of the individual is a primary value in Western democratic society, from a Western perspective, the patient’s ability to make an independent decision is at the center of medical decision making. However, in Eastern cultures, medical decision making is family-centered, accomplished through consensus building. 11

Beauchamp and Childress 3 distinguish between autonomous persons and autonomous choices and stress that it is autonomous choice that is more pertinent to decision making. As stated earlier, persons who make autonomous choices do so with understanding, without influence, and with intentionality. Only intentionality is evaluated as being either present or absent. Choosing with understanding and without influence is evaluated as being more or less fulfilled on a continuous scale. The first criterion for accepting the potential donor’s action as autonomous is whether the potential donor understands all of the risks of the procedure. The second criterion is whether others such as the recipient or another family member are influencing the potential donor. The third and final criterion is whether intention to donate is clearly articulated by the potential donor. These criteria for autonomous choices are directly linked to the elements of informed consent that must be addressed during the donor consent process. The donor must have the capacity to consent, be fully informed of the risks involved in donation, consent freely without coercion to donate, and be aware that he or she can withdraw consent any time before the donation. The health risks will be specific to the type of organ being donated and the health of the donor. Risks for financial burden such as loss of employment or health insurance should also be discussed.

Beauchamp and Childress 3 argue that simply having the capacity for self-governance does not mean that an individual will actually self-govern. Examples of this situation are commonly of a limited or temporary nature such as illness, ignorance, coercion, or restrictions prohibiting self-governance such as residence in prison. Conversely, just as persons capable of autonomous decisions may not exercise their right, persons who are not in many instances perceived as autonomously capable of making decisions can at times make autonomous choices. For example, a 14-year-old does not have the legal capacity of autonomously choosing to donate a kidney to a parent, but if other necessary conditions are met, such as understanding the implications of donating, this child can be permitted to independently choose.

Nonmaleficence

Primum non nocere , “first do no harm,” is believed to be the foundation of medical care. 7 This concept is also known as nonmaleficence. Beauchamp and Childress 3 define harm as “setting back the interests of one party.” Although living donation at first appears to violate this principle, harm is minimized by procedures that mandate that the donor must be healthy as a prerequisite for the procedure. Still, while physical risks are minimized, there is some evidence of risks for psychological distress associated with living donation. In 2 studies of living kidney donors, donation contributed to conflict within their marriage and relationships with their spouses worsened following donation. 12 , 13

Factors to be considered in evaluating risk of harm include type of donation and the donor’s current physical health. For example, the potential for physical impairment associated with the risk of kidney donation is far less than that of liver donation. How risk to individual donors is evaluated is controversial. 8 For example, not all donors are equivocally healthy and they may have a medical problem not estimated to be substantially affected by donating. Presently no consensus has been reached on the degree of ill health in a donor that should be permitted and whether the donor-recipient relationship should be taken into account in this evaluation.

Authors of the consensus statement on live organ donors 14 maintain that the donor-patient relationship should not influence the level of risk permitted for the donor. But Gutmann and Land 15 and Ross et al 2 argue that in the absence of grave risk to the donor’s life or health, additional donor risk should be allowed if a close preexisting emotional relationship existed between the donor and recipient. Ross et al 2 justify their position because of the perceived moral obligation that donors have toward their family member. Further, Glannon and Ross 16 declare that the presence of familial relationships leads to moral obligations to donate. Donors with an emotional attachment also have the potential to gain greater benefits from the procedure than do donors who have no prior emotional relationship with the recipient. Their position is based on the degree of intimacy between the donor and recipient and not on their being biologically related. Spital 17 agrees with Ross et al 2 and Gutmann and Land 15 that the donor who is closely related to the recipient should be permitted to accept more risk but not because of a moral obligation. Instead, greater risk should be allowed because of the common needs and shared interests that generate greater benefits for the donor. For example, the burden of caring for a loved one being treated with dialysis is usually lessened following kidney transplantation.

Beneficence

Beneficence is defined as the obligation to act in the best interests of the individual. 3 Although the benefit to the recipient is clear, in this case, benefit for the donor must also be evaluated. Empirical evidence supports that related donors derive psychological, emotional, and/or spiritual benefits and increased self-esteem from donating. 18 – 20 Following donation, Johnson et al 18 observed a higher quality of life among living kidney donors when compared with the national norm. The personal satisfaction among unrelated or nondirected anonymous donors, however, is unclear.

For donor candidates, there is always the potential for unexpected benefits when treatable medical problems are discovered during the donor evaluation process. In every case of living donation, beneficence is balanced against respect for the donor’s autonomy. It is further balanced against the risk of harm to determine the risk-benefit ratio for donation.

In kidney donation, where the risk of death is 0.005%, the principles of autonomy and beneficence outweigh nonmaleficence. 21 , 22 In liver donation, however, where the risk of death is 0.13%, the calculation is less clear. 21 , 22 Determining the risk-benefit ratio requires evaluation of potential harm to the donor and assessment of anticipated benefits. Nonmaleficence to the donor is proportionate to his or her autonomy and the benefit gained by the donor and recipient. The temporary physical harm to the donor is countered by the psychological benefit gained by aiding the recipient who has a significant need that cannot be fulfilled in a comparable way. To adequately evaluate the risk-benefit ratio, the meaning of benefit and risk of harm to the donor is also balanced against the recipient’s prognosis, as recipients are not equally in need of transplantation. The type and amount of benefit to be realized often relates to the donor’s relationship to the recipient, perhaps most clearly realized within biological relationships.

The parent-child relationship demonstrates the risk-benefit ratio most significantly. Some parents will wish to undergo surgery to benefit their child even if it compromises their own physical health. Consequently, assessing the risk-benefit is sometimes complicated by the same familial relationships that led to the parent offering to be a donor. For example, should one parent risk donation when he or she has other children; or if there is only one child, should one parent possibly risk leaving the recipient without the other parent? A similar question arises when the relationship is reversed and the adult child is the prospective donor volunteering for the parent recipient. If an adult child donates to a parent and the adult child has a family of his or her own, if the underlying disorder responsible for the needed transplant is genetically transmitted, should he or she be a donor when the same disorder might develop in his or her children? It is vital that this issue be addressed in the predonation phase. Which familial relationship should take precedence? How then should potential harm be measured when defined beyond the current physical integrity of the donor? In most cases, donors are encouraged to define harm and work through the process of weighing their risks and benefits. In general, it is the donor who must decide how much potential risk he or she is willing to take on in order to achieve a certain benefit. However, the transplant physician and other transplant professionals are also moral agents who may judge in some instances that organ donation is not ethically acceptable. For example, the risk of harm to the donor may be so great that the procedure would violate the principle of nonmaleficence. The hope for benefit to the recipient may be so small that donation could be viewed as prolonging death and interfering with the recipient’s opportunity to seek palliative care.

With Understanding: Competence to Make Decisions

In the context of living donation, a crucial issue is the competence of the potential donor. Donors must be judged competent before they can make autonomous decisions. The process of informed consent seeks to protect vulnerable groups from exploitation and guarantee autonomous choice by requiring understanding. 23 Beauchamp and Childress 3 posit that persons not generally viewed as autonomous can at times make autonomous choices. Similarly, Biller-Andorno et al 8 reason that decisional capacity depends on what decision is to be made. It follows then that although individuals may be judged incompetent to make financial decisions, for example, this may not be the case for the decision to be a donor. But Biller-Andorno et al 8 further state that in the case of incompetent persons, living donation is justifiable only when minimal risk is involved despite the prospects for secondary gain. Such circumstances can apply to the cognitively impaired and persons younger than 18 years old. For example, a cognitively impaired individual may be permitted to donate a kidney to a brother who is also his guardian but this same individual may not be permitted to donate part of his liver because liver donation is a significantly more risky procedure than kidney donation.

In some instances, the law provides guidance. For example, Germany’s law mandates that donors must be competent and biologically or emotionally related to the recipient. India requires that the donor be an adult and biologically related to the recipient. 8 United States law is silent on the issue of minimum age and competency, requiring only informed consent while prohibiting organ selling. 8 Court decisions have let minors and legally incompetent persons donate when they were biologically related to the recipient and stood to gain substantially from an improvement in the recipient’s health. 8

An argument allowing adolescents to donate is that not all minors are equal in their capacity to understand and evaluate their risk-benefit ratio; the same can also hold true for cognitively impaired individuals. Both classes of persons may adequately comprehend their situation and must be individually evaluated. Furthermore, for minors or cognitively impaired individuals who cannot make their own decision regarding donation, surrogate decision making may not be appropriate. 8 The surrogate decision maker, who is frequently a family member, may not be objective enough to make the decision because he or she may also stand to gain from the procedure.

Without Influence: Freedom to Choose

The process of informed consent is based on objective interpretations of autonomy that deemphasize personal relationships. 23 However, for living donation, the effect and influence of emotion and personal relationships on the capacity for autonomous choice are controversial. 8 For example, the positions of Ross et al 2 and Gutmann and Land 15 discussed earlier are clearly not concordant with the objective view of autonomy. From this perspective, organ donation can occur only when the donor is judged to have chosen to donate without the influence of emotional attachments to the prospective recipient. Autonomous decisions are those made by individuals in isolation from their significant others. In living related donation, however, partiality and personal relationships are often central to the informed consent process. 23 Despite the prevalence of such an individualistic view in bioethics, most transplantation programs have been reluctant to accept anonymous donations from living donors, preferring instead that there be an emotional or familial relationship between the donor and the recipient.

This strict interpretation of autonomy is a nonrelational view in contrast to the relational view, where the donor-recipient relationship is a key aspect of decision making. 8 The relational view presumes that humans are interconnected beings rather than isolated individuals and supports the notion that the overall well-being of the family unit may exceed the rights of the individual members. 8

The nonrelational view is consistent with one end of the continuum representing freedom to choose where consent is totally free and voluntary. The opposite end of the continuum is consent resulting from coercion. Between the 2 extremes is duty or obligation. With the exception of obvious coercion, consensus is lacking regarding which donor-recipient pairs should be allowed to proceed with donation. Of concern is the pressure that potential donors may experience resulting from perceived obligations to their family members. 23 In contrast, Majeske et al 23 contend that the relational view, also referred to by Spital 23 as the “ethics of care,” is inappropriate because it suggests that individuals have a duty to donate to loved ones. Clearly there is a fine line between these 2 circumstances. How much emotional influence should be allowed for consent to be voluntary? Moreover, if someone outside the family must distinguish influence from coercion, “can such a detached external observer adequately appreciate the emotional structure and dynamics of a particular family?” 8

Faden and Beauchamp 23 argue that for coercion to be present and autonomy denied, one person’s will must be forced upon another. However, Spital 23 responds that transplant centers are less concerned about feelings of obligation and more concerned about whether the consent provided genuinely represents the donor’s wishes. The question that then arises is “how can one know when the donor-recipient relationship is strong enough to justify accepting consent that appears to be based on care and concern rather than on full understanding?” 23 This question may be particularly challenging given the work by Schweitzer 24 demonstrating that decisions to donate are often quickly made before full understanding. The new living donor protocols that use paired donation or plasmapheresis therapy make the issue of consent even murkier. Because these protocols allow incompatible individuals to donate, potential donors may believe that they have less excuse to decline donation. However, they can say that they are not willing to donate to a stranger rather than to someone they know. So how then should donor motivation be evaluated?

Intention: Motivation to Donate

Beauchamp and Childress 3 define an intentional act as one that is willed and voluntary. Although Beauchamp and Childress 3 define it as being either present or absent, this may not be completely applicable for living donation because intention is closely related to freedom to choose. One way to examine intention is by evaluating motivation to donate. Lennerling et al 25 conducted in-depth interviews with 12 related (primarily biological) donor-recipient pairs and classified the majority as motivated by the “desire to help.” External pressure was noted in only 1 donor-recipient pair and that pressure came from the recipient’s physician. Of note, investigators in this study interviewed donors during the evaluation process before donation was approved rather than interviewing donors after the procedure. Similar to Schweitzer’s study, the decision to donate was “instantaneous” and typically made before they could be approached by the healthcare provider. Participants in this study stated that donation was the “only option” despite their acknowledgement that other alternatives (eg, for kidney donors, dialysis and deceased donor transplants) existed but with worse outcomes. Transplantation offers longer life and receiving a transplant from a living donor offers better outcomes than receiving a transplant from a deceased donor. This difference is extremely relevant to the decision. In this case, “only option” appears to mean the only or the best option that the donor found acceptable for the recipient.

In light of the preference in the law and clinical practice for an emotional or familial attachment, is an anonymous nondirected donation ethically problematic? Earlier, donor motivation was discussed in reference to the donor’s relationship to the recipient. But what about persons without such a relationship? Regarding unrelated donors, Olbrisch et al 26 ask, “Are we exploiting a vulnerable, potentially pathological group of people, or are we making possible the expression of that which is most positive and uplifting in human nature?” Can acceptability of the motivation for donation be judged independently of the particulars of the donor’s situation? “Does the principle of respect for autonomy require acceptance of anonymous nondirected acts of donation?” 8 For a substantial time, anonymous donations were not permitted because motivations from these donors were questioned. One area of controversy is whether it ought to be permissible to direct an anonymously donated organ to a specific individual or group.

Spital 27 conducted a national poll to explore this issue specifically, regarding public views of directed versus nondirected donations. Forty-seven percent of the 1021 adults polled stated that the donor should be allowed to select a specific person whereas 50% were opposed; a finding without significant differences according to the respondent’s race, ethnicity, sex, or educational level. One quarter stated they would donate a kidney to a stranger and most (93%) would still do so even if they were not able to direct their donation. Less than one third were in favor of allowing directed donation by race or religious group and less than half would permit donation if the potential recipient was advertising for their organ through the media. However, 74% believe directed donation would be acceptable if the designated person was a child (and that were the only request). Spital 27 maintains however, that allowing directed donation would violate the ethical principal of justice because it would permit unequal treatment by allowing some disadvantaged groups to receive less. Additionally, the public may lose faith in transplant centers as a result, hindering future prospects of living donation. Children may be the exception because all persons pass through childhood, but individuals remain 1 race or ethnicity. Also, people feel children are vulnerable and have much life yet to live. Overall, after examining the proportion endorsing such views, Spital 27 estimates that if directed donation were unrestricted, the number of organs would not substantially increase and any such increase would not outweigh the possible harm. Consequently, autonomy of the potential donor is necessarily restricted and donors do not have an unrestricted right to donate. Beauchamp and Childress 3 define rights as “justified claims that individuals and groups can make upon others or upon society.” Most rights however, are not absolute but instead are prima facie, meaning they can be overridden by another’s rights. For living donation, a prospective donor’s right to donate can be overridden by the transplant team’s right not to complete the procedure because their autonomy would be violated. A right to donate involves the belief that an autonomous individual has the inherent privilege of becoming a living donor regardless of the risks involved in the procedure. An example sometimes used to support and illustrate this right is a parent’s decision to rescue their child from oncoming traffic at substantial risk to self. However, this decision can be implemented without the assistance of others, which is not the case for living organ donation requiring the assistance from the transplant team. Consequently, as Spital 17 has stated, “while an autonomous choice is necessary, it is not sufficient [to warrant the procedure] because of the requirement for physician involvement.” As a moral agent, the physician must also believe that the donor’s decision to donate is a reasonable thing to do.

Generally speaking, the consensus in the clinical transplant and ethical theoretical literature is that one begins with assuming the primacy of the individual’s autonomy unless there are clear indications why that autonomy should not be respected. 15 Despite autonomy’s position as a central concept, however, consensus does not exist regarding “its nature and strength or about specific rights of autonomy.” 3 In living donation, the principle of autonomy must be balanced as needed against other ethical principles such as non-maleficence and beneficence.

This article has focused on ethical analysis of living donation using principlism. Other ethical frameworks such as a deontological perspective, mentioned at the start of this article, that focuses on duty and obligation might allow donors to take greater risks than principlism allows. The caring or feminist ethic 28 , 29 may similarly place more emphasis on caring relationships than on autonomy. Future analysis using these frameworks would contribute to the ethical discussion on living donation.

The issue of whether any risks are specific to the new donor protocols is an area in need of future study. Although risks and benefits of living donation for emotionally and biologically related donors are known, it is unclear, for example, whether nondirected donors enjoy the same psychological benefits as do donors involved in directed donation. It is not known whether graft rejection is more or less guilt-inducing for the donor involved in paired donation. Empirical work in these areas will do much to inform the ethical analysis of the new living donor protocols and provide data to be incorporated in the informed consent of individuals donating through these new donor protocols.

- 1. Kohn D. Three-way kidney transplant makes history, happy patients. Baltimore Sun. August 2, 2003: 1a, 6a. [ Google Scholar ]

- 2. Ross LF, Glannon W, Josephson MA, Thistlethwaite JR. Should all living donors be treated equally? Transplantation. 2002;743:418–426. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 3. Beauchamp TL, Childress JF. Principles of Biomedical Ethics. 4th ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1994. [ Google Scholar ]

- 4. The Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network. Available at: www.optn.org/latestData/reptData.asp . Accessed August 27, 2004.

- 5. Nolan MT. Ethical dilemmas in living donor organ transplantation. J Transplant Coord. 1999;9:225–231. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 6. Clouser KD, Gert B. A critique of principlism. J Med Philos. 1990:15: 219–236. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 7. Devettere RJ. Practical Decision Making in Health Care Ethics: Cases and Concepts. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press; 1995. [ Google Scholar ]

- 8. Biller-Andorno N, Agich GJ, Koepkens K, Schauenburg H. Who shall be allowed to give? Living organ donors and the concept of autonomy. Theor Med. 2001;22:351–368. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 9. Ahronheim JC, Moreno JD, Zuckerman C. Ethics in Clinical Practice. 2nd ed. Gaithersburg, Md: Aspen; 2000. [ Google Scholar ]

- 10. Albert PL. Clinical decision making and ethics in communications between donor families and recipients: how much should they know? J Transplant Coord. 1999;9:219–224. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 11. Ruhnke GW, Wilson SR, Akamatsu T, et al. Ethical decision making and patient autonomy: comparison between the United States and Japan. Chest. 2000;118:1172–1182. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 12. Jacobs C, Johnson E, Anderson K, Gillingham K, Matas A. Kidney transplants from living donors: how donation affects family dynamics. Adv Renal Replacement Ther. 1998;5:89–97. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 13. Schover LR, Streem SB, Boparai N, Duriak K, Novick AC. The psychosocial impact of donating a kidney: long-term follow up from a urology based center. J Urol. 1997;157:1596–1601. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 14. Authors for the Live Organ Donor Consensus Group. Consensus statement on the live organ donor. JAMA. 2000;284:2919–2926. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 15. Gutmann T, Land W. Ethics regarding living-donor organ transplantation. Langenbecks Arch Chir. 1999;384:515–522. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 16. Glannon W, Ross RF. Do genetic relationships create moral obligations in organ transplantation? Camb Q Healthc Ethics. 2002;11:153–159. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 17. Spital A. Justification of living-organ donation requires benefit for the donor that balances the risk: commentary on Ross et al. Transplantation. 2002;74:423–424. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 18. Johnson EM, Anderson JK, Jacobs C, et al. Long-term follow-up of living kidney donors: quality of life after donation. Transplantation. 1999;67:717–721. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 19. Iglesias RA, Santiago-Delpin EA, Rive-Mora E, Gonzalez-Caraballo Z, Morales-Otero L. The health of living kidney donors 20 years after donation. Transplant Proc. 2001;33:2041–2042. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 20. Corley MC, Elswick RK, Sargeant CC, Scott S. Attitude, self-image, and quality of life of living kidney donors, Nephrol Nurs J. 2000;27:43–52. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 21. Surman OS. The ethics of partial-liver donation [perspective]. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1038. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 22. Renz JF, Busuttil RW. Adult-to-adult living-donor living transplantation: a critical analysis. Semin Liver Dis. 2000;20:411–424. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 23. Spital A. Ethical issues in living organ donation: donor autonomy and beyond. Am J Kidney Dis. 2001;38:189–195. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 24. Schweitzer J, Seidel-Wiesel M, Verres R, Wiesel M. Psychological consultation before living kidney donation: finding out and handling problem cases. Transplantation. 2003;76:1464–1470. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 25. Lennerling A, Forsberg A, Nyberg G. Becoming a living kidney donor. Transplantation. 2003;76:1243–1247. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 26. Olbrisch ME, Benedict SM, Haller DL, Levenson JL. Psychosocial assessment of living organ donors: clinical and ethical considerations. Prog Transplant. 2001;11:40–49. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 27. Spital A. Should people who donate a kidney to a stranger be permitted to choose their recipients? Views of the United States public. Transplantation. 2003;76:1252–1256. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 28. Gilligan C. In a Different Voice: Psychological Theory and Women’s Development. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press; 1982. [ Google Scholar ]

- 29. Carse AL. The “voice of care”: implications for bioethical education. J Med Philos. 1991;16:5–28. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- View on publisher site

- PDF (113.5 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

Home — Essay Samples — Economics — Donation — The Gift of Life: The Ethics of Organ Donation

The Gift of Life: The Ethics of Organ Donation

- Categories: Donation

About this sample

Words: 551 |

Published: Jun 13, 2024

Words: 551 | Page: 1 | 3 min read

Table of contents

The gift of life: organ donation, the critical need for organ donation, the life-saving benefits of organ donation, dispelling myths and misconceptions, ethical considerations and legislative support.

- United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS). (2021). Facts About Organ Donation.

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2020). Global Observatory on Donation and Transplantation.

- Satel S., & Shwartz M.J.. (2019). When Altruism Isn’t Enough: The Case For Compensating Kidney Donors.

- Taylor J.S., & Caplan A.L.. (2018). The Ethics of Organ Transplants: A Philosophical Perspective.

- Lundin S., & Mouritsen R.. (2017). Organ Transplantation Policy: Ethical Perspectives on Systems Worldwide.

Cite this Essay

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing style below:

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Prof Ernest (PhD)

Verified writer

- Expert in: Economics

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

1 pages / 618 words

2 pages / 703 words

5 pages / 2405 words

2 pages / 857 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Donation

Credit control is absignificant tool used by Reserve Bank of India. It is an important weapon of the monetary policy used to control demand and supply of money which is also termed as liquidity in the economy. Administers of the [...]

A few investigations have been directed on Dividend Policy by various researchers in various time frames. The connection of value instability and dividend yield is very noteworthy as contrast with different factors. (Asghar, [...]

With nearly 47 Million internet users and a GDP rate of 6-7 percent, India represents a digital economy. India has proved to be the biggest market potential for global players. This digital revolution is expected to generate new [...]

Stocks refer to groups of shares in a public limited company. Usually, a company forms stocks when all of its shares that belong to a particular category have been issued and fully paid for. The stock exchange market is [...]

The financial crisis (2008): It is known as the worst economic tragedy since the Great Depression (1929).U.S. Investment bank and Lehman Brothers collapsed due to that crisis. The crisis was the outcome of many sequence events, [...]

Barter System is the medium of exchange between two people for the exchange of goods and services according to their needs. They complete their needs by exchanging goods and services. This system has been used for centuries [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

IMAGES

COMMENTS

This essay on organ donation ethical issues aims to delve into the multifaceted ethical dilemmas surrounding organ donation, exploring the principles, controversies, and challenges that shape this critical aspect of modern healthcare. Say no to plagiarism. Get a tailor-made essay on 'Organ Donation: Analysis of Ethical Issues Involved' ...

Organ Transplants. Organ transplantation is the act of "moving a body organ from one body to another or from a donor site in the patient's own body, to replace the recipient's damaged or absent organ" (Winters, 2000, p. 17).

Organ donation and transplantation encompass a broad spectrum of social, religious, ethical, medical and legal issues. 7 Across and within jurisdictions, there is a plurality of opinion in how best to address organ shortage and to prevent exploitation of vulnerable individuals. In this paper we explore key ethical and legal issues as they relate to three fundamental rules for a morally sound ...

Arguably, while organ donation offers a means through which lives can be saved, ethical and human safety issues surround the practice. Bioethics refers to the study of ethical controversies that emerge in the biological and medical realms.

Moral Issues. The organ transplantation has been long debated and addressed by many scholars from both religious and secular perspective. The major issues concerning the wide permissibility of the act are of bypassing the virtue ethics cardinal features: respect for autonomy, nonmaleficence, beneficence and justice.

Key concepts of principlism and informed consent in living donation. Autonomy. Discussion surrounding ethical justification of living organ donation is usually based on the assumption that the donor is an autonomous person. 8 Autonomy, expressed as self-determination, is the principle of self-governance 9; that is, persons who have the capacity to act intentionally, with understanding, should ...

Unit 1: Organ Donation Name: Kayden Mataafa Class: HED121A Introduction Organ donation within Australia is something society neglects, many barriers prevent Australians from knowing about donation, and how to go about donating. Organ donation is a life-saving and life-transforming medical process.

This essay seeks to delve into the ethical dimensions of organ donation, examining the principles of autonomy, beneficence, and justice, and exploring the contentious issues related to consent, allocation of organs, and the potential for exploitation.

Organ donation and transplantation present many challenges to the medical community and society as a whole that require legal and ethical frameworks. This article sets out the legal framework and key principles of modern bioethics that underpin modern frameworks of organ donation and transplantation practice. In many cases there is no single answer to a problem and the concept is introduced ...

Organ donation is a profound act of generosity that has the power to save multiple lives. A single donor can save up to eight lives by donating organs such as the heart, liver, kidneys, lungs, pancreas, and intestines. Beyond the immediate impact on recipients, organ donation also fosters advancements in medical research and technology.