- Resources ›

- For Students and Parents ›

- Homework Help ›

- Homework Tips ›

How to Write and Structure a Persuasive Speech

- Homework Tips

- Learning Styles & Skills

- Study Methods

- Time Management

- Private School

- College Admissions

- College Life

- Graduate School

- Business School

- Distance Learning

- M.Ed., Education Administration, University of Georgia

- B.A., History, Armstrong State University

The purpose of a persuasive speech is to convince your audience to agree with an idea or opinion that you present. First, you'll need to choose a side on a controversial topic, then you will write a speech to explain your position, and convince the audience to agree with you.

You can produce an effective persuasive speech if you structure your argument as a solution to a problem. Your first job as a speaker is to convince your audience that a particular problem is important to them, and then you must convince them that you have the solution to make things better.

Note: You don't have to address a real problem. Any need can work as the problem. For example, you could consider the lack of a pet, the need to wash one's hands, or the need to pick a particular sport to play as the "problem."

As an example, let's imagine that you have chosen "Getting Up Early" as your persuasion topic. Your goal will be to persuade classmates to get themselves out of bed an hour earlier every morning. In this instance, the problem could be summed up as "morning chaos."

A standard speech format has an introduction with a great hook statement, three main points, and a summary. Your persuasive speech will be a tailored version of this format.

Before you write the text of your speech, you should sketch an outline that includes your hook statement and three main points.

Writing the Text

The introduction of your speech must be compelling because your audience will make up their minds within a few minutes whether or not they are interested in your topic.

Before you write the full body you should come up with a greeting. Your greeting can be as simple as "Good morning everyone. My name is Frank."

After your greeting, you will offer a hook to capture attention. A hook sentence for the "morning chaos" speech could be a question:

- How many times have you been late for school?

- Does your day begin with shouts and arguments?

- Have you ever missed the bus?

Or your hook could be a statistic or surprising statement:

- More than 50 percent of high school students skip breakfast because they just don't have time to eat.

- Tardy kids drop out of school more often than punctual kids.

Once you have the attention of your audience, follow through to define the topic/problem and introduce your solution. Here's an example of what you might have so far:

Good afternoon, class. Some of you know me, but some of you may not. My name is Frank Godfrey, and I have a question for you. Does your day begin with shouts and arguments? Do you go to school in a bad mood because you've been yelled at, or because you argued with your parent? The chaos you experience in the morning can bring you down and affect your performance at school.

Add the solution:

You can improve your mood and your school performance by adding more time to your morning schedule. You can accomplish this by setting your alarm clock to go off one hour earlier.

Your next task will be to write the body, which will contain the three main points you've come up with to argue your position. Each point will be followed by supporting evidence or anecdotes, and each body paragraph will need to end with a transition statement that leads to the next segment. Here is a sample of three main statements:

- Bad moods caused by morning chaos will affect your workday performance.

- If you skip breakfast to buy time, you're making a harmful health decision.

- (Ending on a cheerful note) You'll enjoy a boost to your self-esteem when you reduce the morning chaos.

After you write three body paragraphs with strong transition statements that make your speech flow, you are ready to work on your summary.

Your summary will re-emphasize your argument and restate your points in slightly different language. This can be a little tricky. You don't want to sound repetitive but will need to repeat what you have said. Find a way to reword the same main points.

Finally, you must make sure to write a clear final sentence or passage to keep yourself from stammering at the end or fading off in an awkward moment. A few examples of graceful exits:

- We all like to sleep. It's hard to get up some mornings, but rest assured that the reward is well worth the effort.

- If you follow these guidelines and make the effort to get up a little bit earlier every day, you'll reap rewards in your home life and on your report card.

Tips for Writing Your Speech

- Don't be confrontational in your argument. You don't need to put down the other side; just convince your audience that your position is correct by using positive assertions.

- Use simple statistics. Don't overwhelm your audience with confusing numbers.

- Don't complicate your speech by going outside the standard "three points" format. While it might seem simplistic, it is a tried and true method for presenting to an audience who is listening as opposed to reading.

- 100 Persuasive Speech Topics for Students

- 5 Tips on How to Write a Speech Essay

- Controversial Speech Topics

- How to Write a Graduation Speech as Valedictorian

- How to Give an Impromptu Speech

- 10 Tips for the SAT Essay

- Basic Tips for Memorizing Speeches, Skits, and Plays

- Mock Election Ideas For Students

- 50 Topics for Impromptu Student Speeches

- How to Write an Interesting Biography

- The Difference Between Liberals and Conservatives

- How to Run for Student Council

- Tips to Write a Great Letter to the Editor

- How to Write a Film Review

- Writing the Parts of a Stage Play Script

- 18 Ways to Practice Spelling Words

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

11.2 Persuasive Speaking

Learning objectives.

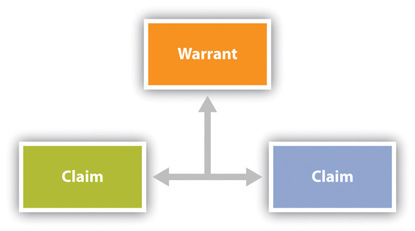

- Explain how claims, evidence, and warrants function to create an argument.

- Identify strategies for choosing a persuasive speech topic.

- Identify strategies for adapting a persuasive speech based on an audience’s orientation to the proposition.

- Distinguish among propositions of fact, value, and policy.

- Choose an organizational pattern that is fitting for a persuasive speech topic.

We produce and receive persuasive messages daily, but we don’t often stop to think about how we make the arguments we do or the quality of the arguments that we receive. In this section, we’ll learn the components of an argument, how to choose a good persuasive speech topic, and how to adapt and organize a persuasive message.

Foundation of Persuasion

Persuasive speaking seeks to influence the beliefs, attitudes, values, or behaviors of audience members. In order to persuade, a speaker has to construct arguments that appeal to audience members. Arguments form around three components: claim, evidence, and warrant. The claim is the statement that will be supported by evidence. Your thesis statement is the overarching claim for your speech, but you will make other claims within the speech to support the larger thesis. Evidence , also called grounds, supports the claim. The main points of your persuasive speech and the supporting material you include serve as evidence. For example, a speaker may make the following claim: “There should be a national law against texting while driving.” The speaker could then support the claim by providing the following evidence: “Research from the US Department of Transportation has found that texting while driving creates a crash risk that is twenty-three times worse than driving while not distracted.” The warrant is the underlying justification that connects the claim and the evidence. One warrant for the claim and evidence cited in this example is that the US Department of Transportation is an institution that funds research conducted by credible experts. An additional and more implicit warrant is that people shouldn’t do things they know are unsafe.

Figure 11.2 Components of an Argument

The quality of your evidence often impacts the strength of your warrant, and some warrants are stronger than others. A speaker could also provide evidence to support their claim advocating for a national ban on texting and driving by saying, “I have personally seen people almost wreck while trying to text.” While this type of evidence can also be persuasive, it provides a different type and strength of warrant since it is based on personal experience. In general, the anecdotal evidence from personal experience would be given a weaker warrant than the evidence from the national research report. The same process works in our legal system when a judge evaluates the connection between a claim and evidence. If someone steals my car, I could say to the police, “I’m pretty sure Mario did it because when I said hi to him on campus the other day, he didn’t say hi back, which proves he’s mad at me.” A judge faced with that evidence is unlikely to issue a warrant for Mario’s arrest. Fingerprint evidence from the steering wheel that has been matched with a suspect is much more likely to warrant arrest.

As you put together a persuasive argument, you act as the judge. You can evaluate arguments that you come across in your research by analyzing the connection (the warrant) between the claim and the evidence. If the warrant is strong, you may want to highlight that argument in your speech. You may also be able to point out a weak warrant in an argument that goes against your position, which you could then include in your speech. Every argument starts by putting together a claim and evidence, but arguments grow to include many interrelated units.

Choosing a Persuasive Speech Topic

As with any speech, topic selection is important and is influenced by many factors. Good persuasive speech topics are current, controversial, and have important implications for society. If your topic is currently being discussed on television, in newspapers, in the lounges in your dorm, or around your family’s dinner table, then it’s a current topic. A persuasive speech aimed at getting audience members to wear seat belts in cars wouldn’t have much current relevance, given that statistics consistently show that most people wear seat belts. Giving the same speech would have been much more timely in the 1970s when there was a huge movement to increase seat-belt use.

Many topics that are current are also controversial, which is what gets them attention by the media and citizens. Current and controversial topics will be more engaging for your audience. A persuasive speech to encourage audience members to donate blood or recycle wouldn’t be very controversial, since the benefits of both practices are widely agreed on. However, arguing that the restrictions on blood donation by men who have had sexual relations with men be lifted would be controversial. I must caution here that controversial is not the same as inflammatory. An inflammatory topic is one that evokes strong reactions from an audience for the sake of provoking a reaction. Being provocative for no good reason or choosing a topic that is extremist will damage your credibility and prevent you from achieving your speech goals.

You should also choose a topic that is important to you and to society as a whole. As we have already discussed in this book, our voices are powerful, as it is through communication that we participate and make change in society. Therefore we should take seriously opportunities to use our voices to speak publicly. Choosing a speech topic that has implications for society is probably a better application of your public speaking skills than choosing to persuade the audience that Lebron James is the best basketball player in the world or that Superman is a better hero than Spiderman. Although those topics may be very important to you, they don’t carry the same social weight as many other topics you could choose to discuss. Remember that speakers have ethical obligations to the audience and should take the opportunity to speak seriously.

You will also want to choose a topic that connects to your own interests and passions. If you are an education major, it might make more sense to do a persuasive speech about funding for public education than the death penalty. If there are hot-button issues for you that make you get fired up and veins bulge out in your neck, then it may be a good idea to avoid those when speaking in an academic or professional context.

Choose a persuasive speech topic that you’re passionate about but still able to approach and deliver in an ethical manner.

Michael Vadon – Nigel Farage – CC BY-SA 2.0.

Choosing such topics may interfere with your ability to deliver a speech in a competent and ethical manner. You want to care about your topic, but you also want to be able to approach it in a way that’s going to make people want to listen to you. Most people tune out speakers they perceive to be too ideologically entrenched and write them off as extremists or zealots.

You also want to ensure that your topic is actually persuasive. Draft your thesis statement as an “I believe” statement so your stance on an issue is clear. Also, think of your main points as reasons to support your thesis. Students end up with speeches that aren’t very persuasive in nature if they don’t think of their main points as reasons. Identifying arguments that counter your thesis is also a good exercise to help ensure your topic is persuasive. If you can clearly and easily identify a competing thesis statement and supporting reasons, then your topic and approach are arguable.

Review of Tips for Choosing a Persuasive Speech Topic

- Not current. People should use seat belts.

- Current. People should not text while driving.

- Not controversial. People should recycle.

- Controversial. Recycling should be mandatory by law.

- Not as impactful. Superman is the best superhero.

- Impactful. Colleges and universities should adopt zero-tolerance bullying policies.

- Unclear thesis. Homeschooling is common in the United States.

- Clear, argumentative thesis with stance. Homeschooling does not provide the same benefits of traditional education and should be strictly monitored and limited.

Adapting Persuasive Messages

Competent speakers should consider their audience throughout the speech-making process. Given that persuasive messages seek to directly influence the audience in some way, audience adaptation becomes even more important. If possible, poll your audience to find out their orientation toward your thesis. I read my students’ thesis statements aloud and have the class indicate whether they agree with, disagree with, or are neutral in regards to the proposition. It is unlikely that you will have a homogenous audience, meaning that there will probably be some who agree, some who disagree, and some who are neutral. So you may employ all of the following strategies, in varying degrees, in your persuasive speech.

When you have audience members who already agree with your proposition, you should focus on intensifying their agreement. You can also assume that they have foundational background knowledge of the topic, which means you can take the time to inform them about lesser-known aspects of a topic or cause to further reinforce their agreement. Rather than move these audience members from disagreement to agreement, you can focus on moving them from agreement to action. Remember, calls to action should be as specific as possible to help you capitalize on audience members’ motivation in the moment so they are more likely to follow through on the action.

There are two main reasons audience members may be neutral in regards to your topic: (1) they are uninformed about the topic or (2) they do not think the topic affects them. In this case, you should focus on instilling a concern for the topic. Uninformed audiences may need background information before they can decide if they agree or disagree with your proposition. If the issue is familiar but audience members are neutral because they don’t see how the topic affects them, focus on getting the audience’s attention and demonstrating relevance. Remember that concrete and proxemic supporting materials will help an audience find relevance in a topic. Students who pick narrow or unfamiliar topics will have to work harder to persuade their audience, but neutral audiences often provide the most chance of achieving your speech goal since even a small change may move them into agreement.

When audience members disagree with your proposition, you should focus on changing their minds. To effectively persuade, you must be seen as a credible speaker. When an audience is hostile to your proposition, establishing credibility is even more important, as audience members may be quick to discount or discredit someone who doesn’t appear prepared or doesn’t present well-researched and supported information. Don’t give an audience a chance to write you off before you even get to share your best evidence. When facing a disagreeable audience, the goal should also be small change. You may not be able to switch someone’s position completely, but influencing him or her is still a success. Aside from establishing your credibility, you should also establish common ground with an audience.

Build common ground with disagreeable audiences and acknowledge areas of disagreement.

Chris-Havard Berge – Shaking Hands – CC BY-NC 2.0.

Acknowledging areas of disagreement and logically refuting counterarguments in your speech is also a way to approach persuading an audience in disagreement, as it shows that you are open-minded enough to engage with other perspectives.

Determining Your Proposition

The proposition of your speech is the overall direction of the content and how that relates to the speech goal. A persuasive speech will fall primarily into one of three categories: propositions of fact, value, or policy. A speech may have elements of any of the three propositions, but you can usually determine the overall proposition of a speech from the specific purpose and thesis statements.

Propositions of fact focus on beliefs and try to establish that something “is or isn’t.” Propositions of value focus on persuading audience members that something is “good or bad,” “right or wrong,” or “desirable or undesirable.” Propositions of policy advocate that something “should or shouldn’t” be done. Since most persuasive speech topics can be approached as propositions of fact, value, or policy, it is a good idea to start thinking about what kind of proposition you want to make, as it will influence how you go about your research and writing. As you can see in the following example using the topic of global warming, the type of proposition changes the types of supporting materials you would need:

- Proposition of fact. Global warming is caused by increased greenhouse gases related to human activity.

- Proposition of value. America’s disproportionately large amount of pollution relative to other countries is wrong .

- Proposition of policy. There should be stricter emission restrictions on individual cars.

To support propositions of fact, you would want to present a logical argument based on objective facts that can then be used to build persuasive arguments. Propositions of value may require you to appeal more to your audience’s emotions and cite expert and lay testimony. Persuasive speeches about policy usually require you to research existing and previous laws or procedures and determine if any relevant legislation or propositions are currently being considered.

“Getting Critical”

Persuasion and Masculinity

The traditional view of rhetoric that started in ancient Greece and still informs much of our views on persuasion today has been critiqued for containing Western and masculine biases. Traditional persuasion has been linked to Western and masculine values of domination, competition, and change, which have been critiqued as coercive and violent (Gearhart, 1979).

Communication scholars proposed an alternative to traditional persuasive rhetoric in the form of invitational rhetoric. Invitational rhetoric differs from a traditional view of persuasive rhetoric that “attempts to win over an opponent, or to advocate the correctness of a single position in a very complex issue” (Bone et al., 2008). Instead, invitational rhetoric proposes a model of reaching consensus through dialogue. The goal is to create a climate in which growth and change can occur but isn’t required for one person to “win” an argument over another. Each person in a communication situation is acknowledged to have a standpoint that is valid but can still be influenced through the offering of alternative perspectives and the invitation to engage with and discuss these standpoints (Ryan & Natalle, 2001). Safety, value, and freedom are three important parts of invitational rhetoric. Safety involves a feeling of security in which audience members and speakers feel like their ideas and contributions will not be denigrated. Value refers to the notion that each person in a communication encounter is worthy of recognition and that people are willing to step outside their own perspectives to better understand others. Last, freedom is present in communication when communicators do not limit the thinking or decisions of others, allowing all participants to speak up (Bone et al., 2008).

Invitational rhetoric doesn’t claim that all persuasive rhetoric is violent. Instead, it acknowledges that some persuasion is violent and that the connection between persuasion and violence is worth exploring. Invitational rhetoric has the potential to contribute to the civility of communication in our society. When we are civil, we are capable of engaging with and appreciating different perspectives while still understanding our own. People aren’t attacked or reviled because their views diverge from ours. Rather than reducing the world to “us against them, black or white, and right or wrong,” invitational rhetoric encourages us to acknowledge human perspectives in all their complexity (Bone et al., 2008).

- What is your reaction to the claim that persuasion includes Western and masculine biases?

- What are some strengths and weaknesses of the proposed alternatives to traditional persuasion?

- In what situations might an invitational approach to persuasion be useful? In what situations might you want to rely on traditional models of persuasion?

Organizing a Persuasive Speech

We have already discussed several patterns for organizing your speech, but some organization strategies are specific to persuasive speaking. Some persuasive speech topics lend themselves to a topical organization pattern, which breaks the larger topic up into logical divisions. Earlier, in Chapter 9 “Preparing a Speech” , we discussed recency and primacy, and in this chapter we discussed adapting a persuasive speech based on the audience’s orientation toward the proposition. These concepts can be connected when organizing a persuasive speech topically. Primacy means putting your strongest information first and is based on the idea that audience members put more weight on what they hear first. This strategy can be especially useful when addressing an audience that disagrees with your proposition, as you can try to win them over early. Recency means putting your strongest information last to leave a powerful impression. This can be useful when you are building to a climax in your speech, specifically if you include a call to action.

Putting your strongest argument last can help motivate an audience to action.

Celestine Chua – The Change – CC BY 2.0.

The problem-solution pattern is an organizational pattern that advocates for a particular approach to solve a problem. You would provide evidence to show that a problem exists and then propose a solution with additional evidence or reasoning to justify the course of action. One main point addressing the problem and one main point addressing the solution may be sufficient, but you are not limited to two. You could add a main point between the problem and solution that outlines other solutions that have failed. You can also combine the problem-solution pattern with the cause-effect pattern or expand the speech to fit with Monroe’s Motivated Sequence.

As was mentioned in Chapter 9 “Preparing a Speech” , the cause-effect pattern can be used for informative speaking when the relationship between the cause and effect is not contested. The pattern is more fitting for persuasive speeches when the relationship between the cause and effect is controversial or unclear. There are several ways to use causes and effects to structure a speech. You could have a two-point speech that argues from cause to effect or from effect to cause. You could also have more than one cause that lead to the same effect or a single cause that leads to multiple effects. The following are some examples of thesis statements that correspond to various organizational patterns. As you can see, the same general topic area, prison overcrowding, is used for each example. This illustrates the importance of considering your organizational options early in the speech-making process, since the pattern you choose will influence your researching and writing.

Persuasive Speech Thesis Statements by Organizational Pattern

- Problem-solution. Prison overcrowding is a serious problem that we can solve by finding alternative rehabilitation for nonviolent offenders.

- Problem–failed solution–proposed solution. Prison overcrowding is a serious problem that shouldn’t be solved by building more prisons; instead, we should support alternative rehabilitation for nonviolent offenders.

- Cause-effect. Prisons are overcrowded with nonviolent offenders, which leads to lesser sentences for violent criminals.

- Cause-cause-effect. State budgets are being slashed and prisons are overcrowded with nonviolent offenders, which leads to lesser sentences for violent criminals.

- Cause-effect-effect. Prisons are overcrowded with nonviolent offenders, which leads to increased behavioral problems among inmates and lesser sentences for violent criminals.

- Cause-effect-solution. Prisons are overcrowded with nonviolent offenders, which leads to lesser sentences for violent criminals; therefore we need to find alternative rehabilitation for nonviolent offenders.

Monroe’s Motivated Sequence is an organizational pattern designed for persuasive speaking that appeals to audience members’ needs and motivates them to action. If your persuasive speaking goals include a call to action, you may want to consider this organizational pattern. We already learned about the five steps of Monroe’s Motivated Sequence in Chapter 9 “Preparing a Speech” , but we will review them here with an example:

- Hook the audience by making the topic relevant to them.

- Imagine living a full life, retiring, and slipping into your golden years. As you get older you become more dependent on others and move into an assisted-living facility. Although you think life will be easier, things get worse as you experience abuse and mistreatment from the staff. You report the abuse to a nurse and wait, but nothing happens and the abuse continues. Elder abuse is a common occurrence, and unlike child abuse, there are no laws in our state that mandate complaints of elder abuse be reported or investigated.

- Cite evidence to support the fact that the issue needs to be addressed.

- According to the American Psychological Association, one to two million elderly US Americans have been abused by their caretakers. In our state, those in the medical, psychiatric, and social work field are required to report suspicion of child abuse but are not mandated to report suspicions of elder abuse.

- Offer a solution and persuade the audience that it is feasible and well thought out.

- There should be a federal law mandating that suspicion of elder abuse be reported and that all claims of elder abuse be investigated.

- Take the audience beyond your solution and help them visualize the positive results of implementing it or the negative consequences of not.

- Elderly people should not have to live in fear during their golden years. A mandatory reporting law for elderly abuse will help ensure that the voices of our elderly loved ones will be heard.

- Call your audience to action by giving them concrete steps to follow to engage in a particular action or to change a thought or behavior.

- I urge you to take action in two ways. First, raise awareness about this issue by talking to your own friends and family. Second, contact your representatives at the state and national level to let them know that elder abuse should be taken seriously and given the same level of importance as other forms of abuse. I brought cards with the contact information for our state and national representatives for this area. Please take one at the end of my speech. A short e-mail or phone call can help end the silence surrounding elder abuse.

Key Takeaways

- Arguments are formed by making claims that are supported by evidence. The underlying justification that connects the claim and evidence is the warrant. Arguments can have strong or weak warrants, which will make them more or less persuasive.

- Good persuasive speech topics are current, controversial (but not inflammatory), and important to the speaker and society.

- When audience members agree with the proposal, focus on intensifying their agreement and moving them to action.

- When audience members are neutral in regards to the proposition, provide background information to better inform them about the issue and present information that demonstrates the relevance of the topic to the audience.

- When audience members disagree with the proposal, focus on establishing your credibility, build common ground with the audience, and incorporate counterarguments and refute them.

- Propositions of fact focus on establishing that something “is or isn’t” or is “true or false.”

- Propositions of value focus on persuading an audience that something is “good or bad,” “right or wrong,” or “desirable or undesirable.”

- Propositions of policy advocate that something “should or shouldn’t” be done.

- Persuasive speeches can be organized using the following patterns: problem-solution, cause-effect, cause-effect-solution, or Monroe’s Motivated Sequence.

- Getting integrated: Give an example of persuasive messages that you might need to create in each of the following contexts: academic, professional, personal, and civic. Then do the same thing for persuasive messages you may receive.

- To help ensure that your persuasive speech topic is persuasive and not informative, identify the claims, evidence, and warrants you may use in your argument. In addition, write a thesis statement that refutes your topic idea and identify evidence and warrants that could support that counterargument.

- Determine if your speech is primarily a proposition of fact, value, or policy. How can you tell? Identify an organizational pattern that you think will work well for your speech topic, draft one sentence for each of your main points, and arrange them according to the pattern you chose.

Bone, J. E., Cindy L. Griffin, and T. M. Linda Scholz, “Beyond Traditional Conceptualizations of Rhetoric: Invitational Rhetoric and a Move toward Civility,” Western Journal of Communication 72 (2008): 436.

Gearhart, S. M., “The Womanization of Rhetoric,” Women’s Studies International Quarterly 2 (1979): 195–201.

Ryan, K. J., and Elizabeth J. Natalle, “Fusing Horizons: Standpoint Hermenutics and Invitational Rhetoric,” Rhetoric Society Quarterly 31 (2001): 69–90.

Communication in the Real World Copyright © 2016 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

A Guide to Effective Communication: What is Persuasive Speech?

- By Judhajit Sen

- April 5, 2024

Key Takeaways

- A persuasive speech is a type of speech that aims to change someone’s mind, whether for a business presentation or conference, by making them believe, feel, or do something.

- To deliver a speech that is persuasive, begin by defining your goal clearly and communicating it early in your speech to establish trust with your audience.

- Make a strong first impression with an attention-grabbing introduction that establishes credibility and sets the stage for your message.

- Know your audience and tailor your type of speech to resonate with their interests, concerns, and attitudes to increase persuasiveness.

- Choose the most persuasive speech ideas supported by objective research and evidence, and organize them logically with smooth transitions for audience engagement .

- Address opposing viewpoints respectfully to strengthen your argument and enhance credibility, demonstrating thorough research and consideration of different perspectives.

- Leave a lasting impression with a compelling conclusion that reinforces your main points and motivates action through a clear call to action.

Persuasive Speech: What is it?

A persuasive speech aims to change someone’s mind so they agree with you. This could be for a business presentation or conference. Before you talk, you should learn how to write a persuasive speech. This helps you be ready, think about what you want to say, and make sure everything is true.

Giving a persuasive speech is a way to make people believe, feel, or do something. Whether you’re at work, leading a team, or managing social media, persuasive speaking is a big part of your communication skills.

Persuasive speeches try to make people think or act differently. They use facts, stories, and other reasons to convince the audience. The goal is to get people to agree with your ideas.

But not every speech will convince everyone. Success is measured by how much the audience members consider your argument.

The purpose of a persuasive public speaking is to inform, teach, and convince people. You want them to see things your way. It’s important to talk about something you know well and can argue for convincingly.

When giving a speech that is persuasive, the speaker’s credibility, emotions, and logical arguments are key. They use words, visuals, and body language to sway the audience.

Elements of a Good Persuasive Speech

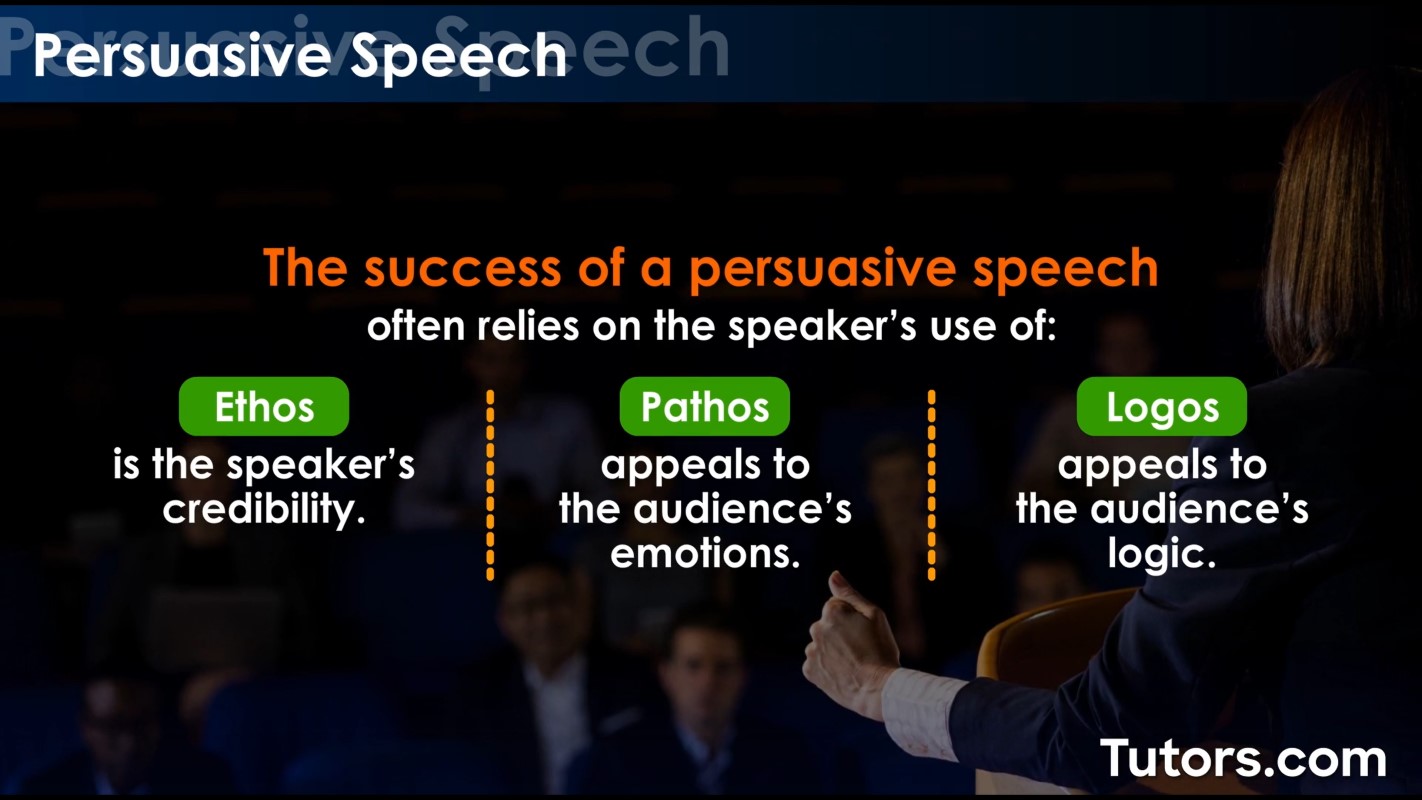

A successful persuasive speech relies on three components of rhetoric: ethos, pathos, and logos.

Ethos: Establishing credibility is essential. A speaker must demonstrate knowledge, trustworthiness, and ethical conduct to gain the audience’s respect. Confidence, expertise, and relevant experience are crucial in building credibility.

Pathos: Emotional appeal is a powerful tool in persuasion. By tapping into the audience’s emotions, a speaker can create a connection and evoke feelings such as empathy, compassion, or fear. Stories, metaphors, and vivid language can effectively appeal to emotions.

Logos: Logical appeal strengthens the persuasive argument. Providing concrete evidence, facts, statistics, and expert validation supports the speaker’s claims and enhances the credibility of the message. This approach appeals to the audience’s sense of reason and logic.

In crafting a persuasive speech, it’s important to incorporate elements of all three appeals to effectively engage the audience and convey a compelling message. Ethos establishes credibility, pathos connects emotionally, and logos provides logical reasoning, ensuring a well-rounded and persuasive approach.

Tips To Craft A Good Persuasive Speech

Define Your Goal

When crafting your speech, it’s essential to define your goal clearly. Knowing what you want to achieve helps you stay focused and organize your argument effectively. Make sure to communicate your goal early in your speech to establish trust with your audience.

Choose a topic. Consider what you’re speaking on and what action you want your audience to take. Do you want them to sign a petition, contact their legislator, boycott a product, or something else? Your conclusion should include a call to action that aligns with your persuasive message.

Make A Strong First Impression

Your introduction is your chance to make a strong first impression and set the tone for your speech. It’s crucial in grabbing your audience’s attention and establishing credibility.

To start, craft an opening that is attention-grabbing, whether through humor, emotion, or a shocking fact. Engage your audience by involving them. Tell a story and use examples. It’s also important to showcase your credentials to establish trust.

Make sure your introduction clearly introduces the topic of your speech after capturing your audience’s attention. This sets the stage for the rest of your persuasive message

Know Your Audience

Knowing your audience is essential for a persuasive speech. Before you start writing, think about what you want the audience to do. Consider their age, gender, culture, and shared interests. Understanding their attitudes and concerns will help you tailor your speech to resonate with them.

Put yourself in your audience’s shoes. Think about their dreams, worries, and what they do. How will your speech benefit them or solve a problem they care about? Addressing their concerns and resistance points will make your message more persuasive.

Remember, your audience may already have different opinions. Focus on those who are undecided. Tailoring your speech to their concerns will allow the audience to accept your point of view.

Provide background information if needed, and avoid using complicated language. If your audience already agrees with you, it may be easier to persuade them. But if they have opposing views, use additional facts and evidence to support your argument. Understanding your audience is the key to influencing them effectively.

Choose The Most Persuasive Points

When preparing your speech, focus on distilling your research into a few powerful arguments. Choose the most persuasive points that you’re passionate about and believe will sway your audience. Select between two to four key arguments to maintain their interest.

Selecting two to four themes to discuss within the speech allows you enough time to explain your viewpoint thoroughly. Ensure each point transitions smoothly into the next for a logical flow. Use connecting sentences to make your speech easy to follow.

Back up your arguments with objective research, not just your opinion. Utilize examples, analogies, and stories to make your topic relatable to the audience. This approach increases the likelihood of persuading them to your viewpoint.

Organize your main points using an outline, considering the time you have to speak. You can effectively make your case in under 10 minutes, keeping the audience engaged. Aim for three or four supporting points, providing examples and reasons for each. Use evidence-based facts and real-life examples to strengthen your argument and appeal to the audience’s emotions. Ensure your evidence flows logically to complete your argument.

Understand The Opposing Viewpoints

To make your speech more persuasive, it’s crucial to research the topic thoroughly. Look for information from reliable sources like universities or news outlets. Also, understand the opposing viewpoints. This will help you address them during your speech and possibly sway listeners who disagree with you.

Many people in your audience might doubt your viewpoint, so it’s essential to acknowledge and respond to their objections. This shows that you understand their concerns and can answer their questions.

A good persuasive speech addresses and disputes counter-arguments. By doing this, you strengthen your argument and show that you’ve considered different perspectives. When discussing opposing views, be fair and explain them without bias. This shows respect for your audience and demonstrates your reasoned judgment.

Acknowledging and addressing counterarguments not only demonstrates your research but also helps alleviate any doubts or concerns your audience may have. It’s an important part of making your speech effective.

Leave A Lasting Impression

The conclusion of your persuasive speech is your final opportunity to leave a lasting impression on your audience. It should be strong and memorable, leaving them with a clear understanding of your message.

Consider emphasizing your strongest argument or reinforcing key points made throughout your speech. This ensures that your closing argument is what sticks with your audience.

Craft a compelling closing line that encapsulates your message and motivates action. End with a call to action that summarizes your main points and encourages your audience to take a specific step, such as signing a petition or supporting a cause.

By restating your main points and reinforcing the importance of your message, you can leave your audience feeling inspired and empowered to act.

Crafting an Effective Persuasive Speech

Crafting a persuasive speech requires careful consideration of several key elements to ensure its effectiveness. By understanding and incorporating these elements, you can create a speech that captivates your audience and persuades them to your viewpoint.

Begin by defining your goal clearly and communicating it early in your speech. Whether you aim to inform, educate, or motivate, clarity of purpose is essential in engaging your audience.

A strong introduction sets the stage for your speech, grabbing your audience’s attention and establishing credibility. Start with an attention-grabbing statement or anecdote, and showcase your expertise to build trust with your audience.

Know your audience and tailor your speech to resonate with their interests, concerns, and attitudes. By addressing their needs and providing relevant information, you can effectively persuade them to your viewpoint.

Choose the most persuasive points to support your argument, and back them up with objective research and evidence. Organize your main points logically and ensure smooth transitions between them to maintain your audience’s engagement.

Address opposing viewpoints with fairness and respect, acknowledging and responding to objections to strengthen your argument. By demonstrating thorough research and consideration of different perspectives, you can enhance the credibility of your speech.

Finally, leave a lasting impression with a compelling conclusion that reinforces your main points and motivates action. End with a call to action that summarizes your message and encourages your audience to take a specific step towards your goal.

Incorporating these elements into your persuasive speech will help you craft a compelling and impactful message that resonates with your audience and achieves your objectives.

1. What is a persuasive speech?

A persuasive speech aims to change someone’s mind so they agree with you. It could be for a business presentation or conference. Before speaking, it’s important to write your speech first, ensuring you’re ready, clear about what you want to say, and that everything you say is true.

2. What are the main goals of a persuasive speech?

The main goals are to inform, teach, and convince people. You want them to see things your way. It’s crucial to talk about something you know well and can argue convincingly.

3. What are the key elements of a persuasive speech?

A successful persuasive speech relies on three main elements of rhetoric: ethos (credibility), pathos (emotional appeal), and logos (logical appeal). These elements help in building trust, connecting emotionally, and providing logical reasoning to persuade the audience.

4. How can I make my persuasive speech effective?

Craft your speech with a clear goal in mind, making a strong first impression with an attention-grabbing introduction. Know your audience and tailor your message to resonate with them. Choose persuasive points supported by evidence, address opposing viewpoints respectfully, and leave a lasting impression with a compelling conclusion and call to action.

5. What should I include in the conclusion of my persuasive speech?

The conclusion should restate your main points and reinforce the importance of your message. End with a compelling call to action that summarizes your message and motivates your audience to take a specific step towards your goal.

Unlock Your Persuasive Potential with Zenith Learning

Discover how to captivate your audience and deliver compelling speeches with Prezentium’s Zenith Learning workshops. Our interactive programs combine structured problem-solving with visual storytelling techniques to empower you to:

- Capture Audience Attention: Learn why your audience matters and how to engage them effectively from the start.

- Master Story-Lining: Understand how to structure your message and use various storytelling techniques to deliver impactful presentations.

- Nail C-suite Presentations: Discover the secret sauce to delivering persuasive presentations that leave a lasting impression on executives.

- Communicate Complex Ideas Simply: Learn how to convey even the most complex ideas using simple layouts and visualization techniques.

- Present with Confidence: Harness the power of your voice and body language to present confidently and command attention.

- Master Persuasion Techniques: Learn advanced persuasion techniques and theater skills to build presence and command the room.

Empower yourself and your team to make persuasive speeches and presentations that drive results. Join our Zenith Learning workshops today and unlock your persuasive potential!

Why wait? Avail a complimentary 1-on-1 session with our presentation expert. See how other enterprise leaders are creating impactful presentations with us.

Business Gantt Chart Examples for Project Management, and More

Organizational communication: how to communicate effectively, elements of communication: 9 elements of the communication process.

Chapter 6: Elements of Persuasive Speaking

In this chapter you will be introduced to Ethos, Pathos, and Logos. These elements of rhetoric and persuasion are vital to our speeches. Ethos will encourage you to consider your credibility as a speaker, pathos will ask you to engage with your audience and consider their perspective and ways in which you can further their emotional connection to your topic, and logos will guide the logic of your speech. Public speakers that utilize all three, ethos, pathos, and logos, are setting themselves up for success in their speech delivery. We will also review Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs as a theoretical underpinning to the development of a persuasive speech by tailoring the message to our audience. The audience is key to your speech; it is important to truly consider the needs of the listeners. Lastly, we will learn how to organize our persuasive speeches through an organizational pattern called Monroe’s Motivated Sequence. If you read through the material and apply the concepts, you will be well on your way to delivering a strong persuasive speech.

Public Speaking Copyright © by Dr. Layne Goodman; Amber Green, M.A.; and Various is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Persuasive Speeches — Types, Topics, and Examples

What is a persuasive speech?

In a persuasive speech, the speaker aims to convince the audience to accept a particular perspective on a person, place, object, idea, etc. The speaker strives to cause the audience to accept the point of view presented in the speech.

The success of a persuasive speech often relies on the speaker’s use of ethos, pathos, and logos.

Ethos is the speaker’s credibility. Audiences are more likely to accept an argument if they find the speaker trustworthy. To establish credibility during a persuasive speech, speakers can do the following:

Use familiar language.

Select examples that connect to the specific audience.

Utilize credible and well-known sources.

Logically structure the speech in an audience-friendly way.

Use appropriate eye contact, volume, pacing, and inflection.

Pathos appeals to the audience’s emotions. Speakers who create an emotional bond with their audience are typically more convincing. Tapping into the audience’s emotions can be accomplished through the following:

Select evidence that can elicit an emotional response.

Use emotionally-charged words. (The city has a problem … vs. The city has a disease …)

Incorporate analogies and metaphors that connect to a specific emotion to draw a parallel between the reference and topic.

Utilize vivid imagery and sensory words, allowing the audience to visualize the information.

Employ an appropriate tone, inflection, and pace to reflect the emotion.

Logos appeals to the audience’s logic by offering supporting evidence. Speakers can improve their logical appeal in the following ways:

Use comprehensive evidence the audience can understand.

Confirm the evidence logically supports the argument’s claims and stems from credible sources.

Ensure that evidence is specific and avoid any vague or questionable information.

Types of persuasive speeches

The three main types of persuasive speeches are factual, value, and policy.

A factual persuasive speech focuses solely on factual information to prove the existence or absence of something through substantial proof. This is the only type of persuasive speech that exclusively uses objective information rather than subjective. As such, the argument does not rely on the speaker’s interpretation of the information. Essentially, a factual persuasive speech includes historical controversy, a question of current existence, or a prediction:

Historical controversy concerns whether an event happened or whether an object actually existed.

Questions of current existence involve the knowledge that something is currently happening.

Predictions incorporate the analysis of patterns to convince the audience that an event will happen again.

A value persuasive speech concerns the morality of a certain topic. Speakers incorporate facts within these speeches; however, the speaker’s interpretation of those facts creates the argument. These speeches are highly subjective, so the argument cannot be proven to be absolutely true or false.

A policy persuasive speech centers around the speaker’s support or rejection of a public policy, rule, or law. Much like a value speech, speakers provide evidence supporting their viewpoint; however, they provide subjective conclusions based on the facts they provide.

How to write a persuasive speech

Incorporate the following steps when writing a persuasive speech:

Step 1 – Identify the type of persuasive speech (factual, value, or policy) that will help accomplish the goal of the presentation.

Step 2 – Select a good persuasive speech topic to accomplish the goal and choose a position .

Step 3 – Locate credible and reliable sources and identify evidence in support of the topic/position. Revisit Step 2 if there is a lack of relevant resources.

Step 4 – Identify the audience and understand their baseline attitude about the topic.

Step 5 – When constructing an introduction , keep the following questions in mind:

What’s the topic of the speech?

What’s the occasion?

Who’s the audience?

What’s the purpose of the speech?

Step 6 – Utilize the evidence within the previously identified sources to construct the body of the speech. Keeping the audience in mind, determine which pieces of evidence can best help develop the argument. Discuss each point in detail, allowing the audience to understand how the facts support the perspective.

Step 7 – Addressing counterarguments can help speakers build their credibility, as it highlights their breadth of knowledge.

Step 8 – Conclude the speech with an overview of the central purpose and how the main ideas identified in the body support the overall argument.

Persuasive speech outline

One of the best ways to prepare a great persuasive speech is by using an outline. When structuring an outline, include an introduction, body, and conclusion:

Introduction

Attention Grabbers

Ask a question that allows the audience to respond in a non-verbal way; ask a rhetorical question that makes the audience think of the topic without requiring a response.

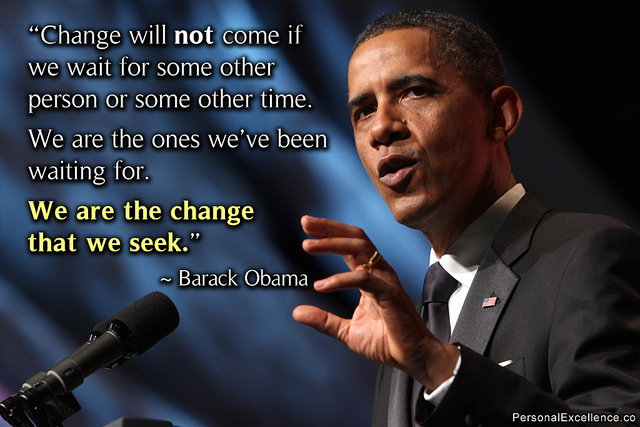

Incorporate a well-known quote that introduces the topic. Using the words of a celebrated individual gives credibility and authority to the information in the speech.

Offer a startling statement or information about the topic, typically done using data or statistics.

Provide a brief anecdote or story that relates to the topic.

Starting a speech with a humorous statement often makes the audience more comfortable with the speaker.

Provide information on how the selected topic may impact the audience .

Include any background information pertinent to the topic that the audience needs to know to understand the speech in its entirety.

Give the thesis statement in connection to the main topic and identify the main ideas that will help accomplish the central purpose.

Identify evidence

Summarize its meaning

Explain how it helps prove the support/main claim

Evidence 3 (Continue as needed)

Support 3 (Continue as needed)

Restate thesis

Review main supports

Concluding statement

Give the audience a call to action to do something specific.

Identify the overall importan ce of the topic and position.

Persuasive speech topics

The following table identifies some common or interesting persuasive speech topics for high school and college students:

Persuasive speech examples

The following list identifies some of history’s most famous persuasive speeches:

John F. Kennedy’s Inaugural Address: “Ask Not What Your Country Can Do for You”

Lyndon B. Johnson: “We Shall Overcome”

Marc Antony: “Friends, Romans, Countrymen…” in William Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar

Ronald Reagan: “Tear Down this Wall”

Sojourner Truth: “Ain’t I a Woman?”

My Speech Class

Public Speaking Tips & Speech Topics

How to Write an Outline for a Persuasive Speech, with Examples

Jim Peterson has over 20 years experience on speech writing. He wrote over 300 free speech topic ideas and how-to guides for any kind of public speaking and speech writing assignments at My Speech Class.

Persuasive speeches are one of the three most used speeches in our daily lives. Persuasive speech is used when presenters decide to convince their presentation or ideas to their listeners. A compelling speech aims to persuade the listener to believe in a particular point of view. One of the most iconic examples is Martin Luther King’s ‘I had a dream’ speech on the 28th of August 1963.

In this article:

What is Persuasive Speech?

Here are some steps to follow:, persuasive speech outline, final thoughts.

Persuasive speech is a written and delivered essay to convince people of the speaker’s viewpoint or ideas. Persuasive speaking is the type of speaking people engage in the most. This type of speech has a broad spectrum, from arguing about politics to talking about what to have for dinner. Persuasive speaking is highly connected to the audience, as in a sense, the speaker has to meet the audience halfway.

Persuasive Speech Preparation

Persuasive speech preparation doesn’t have to be difficult, as long as you select your topic wisely and prepare thoroughly.

1. Select a Topic and Angle

Come up with a controversial topic that will spark a heated debate, regardless of your position. This could be about anything. Choose a topic that you are passionate about. Select a particular angle to focus on to ensure that your topic isn’t too broad. Research the topic thoroughly, focussing on key facts, arguments for and against your angle, and background.

2. Define Your Persuasive Goal

Once you have chosen your topic, it’s time to decide what your goal is to persuade the audience. Are you trying to persuade them in favor of a certain position or issue? Are you hoping that they change their behavior or an opinion due to your speech? Do you want them to decide to purchase something or donate money to a cause? Knowing your goal will help you make wise decisions about approaching writing and presenting your speech.

3. Analyze the Audience

Understanding your audience’s perspective is critical anytime that you are writing a speech. This is even more important when it comes to a persuasive speech because not only are you wanting to get the audience to listen to you, but you are also hoping for them to take a particular action in response to your speech. First, consider who is in the audience. Consider how the audience members are likely to perceive the topic you are speaking on to better relate to them on the subject. Grasp the obstacles audience members face or have regarding the topic so you can build appropriate persuasive arguments to overcome these obstacles.

Can We Write Your Speech?

Get your audience blown away with help from a professional speechwriter. Free proofreading and copy-editing included.

4. Build an Effective Persuasive Argument

Once you have a clear goal, you are knowledgeable about the topic and, have insights regarding your audience, you will be ready to build an effective persuasive argument to deliver in the form of a persuasive speech.

Start by deciding what persuasive techniques are likely to help you persuade your audience. Would an emotional and psychological appeal to your audience help persuade them? Is there a good way to sway the audience with logic and reason? Is it possible that a bandwagon appeal might be effective?

5. Outline Your Speech

Once you know which persuasive strategies are most likely to be effective, your next step is to create a keyword outline to organize your main points and structure your persuasive speech for maximum impact on the audience.

Start strong, letting your audience know what your topic is, why it matters and, what you hope to achieve at the end of your speech. List your main points, thoroughly covering each point, being sure to build the argument for your position and overcome opposing perspectives. Conclude your speech by appealing to your audience to act in a way that will prove that you persuaded them successfully. Motivation is a big part of persuasion.

6. Deliver a Winning Speech

Select appropriate visual aids to share with your audiences, such as graphs, photos, or illustrations. Practice until you can deliver your speech confidently. Maintain eye contact, project your voice and, avoid using filler words or any form of vocal interference. Let your passion for the subject shine through. Your enthusiasm may be what sways the audience.

Topic: What topic are you trying to persuade your audience on?

Specific Purpose:

Central idea:

- Attention grabber – This is potentially the most crucial line. If the audience doesn’t like the opening line, they might be less inclined to listen to the rest of your speech.

- Thesis – This statement is used to inform the audience of the speaker’s mindset and try to get the audience to see the issue their way.

- Qualifications – Tell the audience why you are qualified to speak about the topic to persuade them.

After the introductory portion of the speech is over, the speaker starts presenting reasons to the audience to provide support for the statement. After each reason, the speaker will list examples to provide a factual argument to sway listeners’ opinions.

- Example 1 – Support for the reason given above.

- Example 2 – Support for the reason given above.

The most important part of a persuasive speech is the conclusion, second to the introduction and thesis statement. This is where the speaker must sum up and tie all of their arguments into an organized and solid point.

- Summary: Briefly remind the listeners why they should agree with your position.

- Memorable ending/ Audience challenge: End your speech with a powerful closing thought or recommend a course of action.

- Thank the audience for listening.

Persuasive Speech Outline Examples

Topic: Walking frequently can improve both your mental and physical health.

Specific Purpose: To persuade the audience to start walking to improve their health.

Central idea: Regular walking can improve your mental and physical health.

Life has become all about convenience and ease lately. We have dishwashers, so we don’t have to wash dishes by hand with electric scooters, so we don’t have to paddle while riding. I mean, isn’t it ridiculous?

Today’s luxuries have been welcomed by the masses. They have also been accused of turning us into passive, lethargic sloths. As a reformed sloth, I know how easy it can be to slip into the convenience of things and not want to move off the couch. I want to persuade you to start walking.

Americans lead a passive lifestyle at the expense of their own health.

- This means that we spend approximately 40% of our leisure time in front of the TV.

- Ironically, it is also reported that Americans don’t like many of the shows that they watch.

- Today’s studies indicate that people were experiencing higher bouts of depression than in the 18th and 19th centuries, when work and life were considered problematic.

- The article reports that 12.6% of Americans suffer from anxiety, and 9.5% suffer from severe depression.

- Present the opposition’s claim and refute an argument.

- Nutritionist Phyllis Hall stated that we tend to eat foods high in fat, which produces high levels of cholesterol in our blood, which leads to plaque build-up in our arteries.

- While modifying our diet can help us decrease our risk for heart disease, studies have indicated that people who don’t exercise are at an even greater risk.

In closing, I urge you to start walking more. Walking is a simple, easy activity. Park further away from stores and walk. Walk instead of driving to your nearest convenience store. Take 20 minutes and enjoy a walk around your neighborhood. Hide the TV remote, move off the couch and, walk. Do it for your heart.

Thank you for listening!

Topic: Less screen time can improve your sleep.

Specific Purpose: To persuade the audience to stop using their screens two hours before bed.

Central idea: Ceasing electronics before bed will help you achieve better sleep.

Who doesn’t love to sleep? I don’t think I have ever met anyone who doesn’t like getting a good night’s sleep. Sleep is essential for our bodies to rest and repair themselves.

I love sleeping and, there is no way that I would be able to miss out on a good night’s sleep.

As someone who has had trouble sleeping due to taking my phone into bed with me and laying in bed while entertaining myself on my phone till I fall asleep, I can say that it’s not the healthiest habit, and we should do whatever we can to change it.

- Our natural blue light source is the sun.

- Bluelight is designed to keep us awake.

- Bluelight makes our brain waves more active.

- We find it harder to sleep when our brain waves are more active.

- Having a good night’s rest will improve your mood.

- Being fully rested will increase your productivity.

Using electronics before bed will stimulate your brainwaves and make it more difficult for you to sleep. Bluelight tricks our brains into a false sense of daytime and, in turn, makes it more difficult for us to sleep. So, put down those screens if you love your sleep!

Thank the audience for listening

A persuasive speech is used to convince the audience of the speaker standing on a certain subject. To have a successful persuasive speech, doing the proper planning and executing your speech with confidence will help persuade the audience of your standing on the topic you chose. Persuasive speeches are used every day in the world around us, from planning what’s for dinner to arguing about politics. It is one of the most widely used forms of speech and, with proper planning and execution, you can sway any audience.

How to Write the Most Informative Essay

How to Craft a Masterful Outline of Speech

Leave a Comment

I accept the Privacy Policy

Reach out to us for sponsorship opportunities

Vivamus integer non suscipit taciti mus etiam at primis tempor sagittis euismod libero facilisi.

© 2024 My Speech Class

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

57 Constructing a Persuasive Speech

In a sense, constructing your persuasive speech is the culmination of the skills you have learned already. In another sense, you are challenged to think somewhat differently. While the steps of analyzing your audience, formulating your purpose and central idea, applying evidence, considering ethics, framing the ideas in appropriate language, and then practicing delivery will of course apply, you will need to consider some expanded options about each of these steps.

Formulating a Proposition

As mentioned before, when thinking about a central idea statement in a persuasive speech, we use the terms “proposition” or claim. Persuasive speeches have one of four types of propositions or claims, which deter- mine your overall approach. Before you move on, you need to determine what type of proposition you should have (based on the audience, context, issues involved in the topic, and assignment for the class).

Proposition of Fact

Speeches with this type of proposition attempt to establish the truth of a statement. The core of the proposition (or claim) is not whether something is morally right and wrong or what should be done about the topic, only that a statement is supported by evidence or not. These propositions are not facts such as “the chemical symbol for water is H20” or “Barack Obama won the presidency in 2008 with 53% of the vote.” Propositions or claims of fact are statements over which persons disagree and there is evidence on both sides, although probably more on one than the other. Some examples of propositions of fact are:

Converting to solar energy can save homeowners money.

John F. Kennedy was assassinated by Lee Harvey Oswald working alone.

Experiments using animals are essential to the development of many life-saving medical procedures.

Climate change has been caused by human activity.

Granting tuition tax credits to the parents of children who attend private schools will perpetuate educational inequality.

Watching violence on television causes violent behavior in children.

William Shakespeare did not write most of the plays attributed to him.

John Doe committed the crime of which he is accused.

Notice that in none of these are any values—good or bad—mentioned. Perpetuating segregation is not portrayed as good or bad, only as an effect of a policy. Of course, most people view educational inequality negatively, just as they view life-saving medical procedures positively. But the point of these propositions is to prove with evidence the truth of a statement, not its inherent value or what the audience should do about it. In fact, in some propositions of fact no action response would even be possible, such as the proposition listed above that Lee Harvey Oswald acted alone in the assassination of President Kennedy.

Proposition of Definition

This is probably not one that you will use in your class, but it bears mentioning here because it is used in legal and scholarly arguments. Propositions of definitions argue that a word, phrase, or concept has a particular meaning. Remembering back to Chapter 7 on supporting materials, we saw that there are various ways to define words, such as by negation, operationalizing, and classification and division. It may be important for you to define your terms, especially if you have a value proposition. Lawyers, legislators, and scholars often write briefs, present speeches, or compose articles to define terms that are vital to defendants, citizens, or disciplines. We saw a proposition of definition defended in the Supreme Court’s 2015 decision to redefine marriage laws as applying to same-sex couples, based on arguments presented in court. Other examples might be:

The Second Amendment to the Constitution does not include possession of automatic weapons for private use.

Alcoholism should be considered a disease because…

The action committed by Mary Smith did not meet the standard for first-degree murder.

Thomas Jefferson’s definition of inalienable rights did not include a right to privacy.

In each of these examples, the proposition is that the definition of these things (the Second Amendment, alcoholism, crime, and inalienable rights) needs to be changed or viewed differently, but the audience is not asked to change an attitude or action.

Propositions of Value

It is likely that you or some of your classmates will give speeches with propositions of value. When the proposition has a word such as “good,” “bad,” “best,” “worst,” “just,” “unjust,” “ethical,” “unethical,” “moral,” “immoral,” “beneficial,” “harmful,” “advantageous,” or “disadvantageous,” it is a proposition of value. Some examples include:

Hybrid cars are the best form of automobile transportation available today.

Homeschooling is more beneficial for children than traditional schooling.

The War in Iraq was not justified. Capital punishment is morally wrong.

Mascots that involve Native American names, characters, and symbols are demeaning.

A vegan diet is the healthiest one for adults.

Propositions of value require a first step: defining the “value” word. If a war is unjustified, what makes a war “just” or “justified” in the first place? That is a fairly philosophical question. What makes a form of transportation “best” or “better” than another? Isn’t that a matter of personal approach? For different people, “best” might mean “safest,” “least expensive,” “most environmentally responsible,” “stylish,” “powerful,” or “prestigious.” Obviously, in the case of the first proposition above, it means “environmentally responsible.” It would be the first job of the speaker, after introducing the speech and stating the proposition, to explain what “best form of automobile transportation” means. Then the proposition would be defended with separate arguments.

Propositions of Policy

These propositions are easy to identify because they almost always have the word “should” in them. These propositions call for a change in policy or practice (including those in a government, community, or school), or they can call for the audience to adopt a certain behavior. Speeches with propositions of policy can be those that call for passive acceptance and agreement from the audience and those that try to instigate the audience to action, to actually do something immediately or in the long-term.

Our state should require mandatory recertification of lawyers every ten years.

The federal government should act to ensure clean water standards for all citizens.

The federal government should not allow the use of technology to choose the sex of an unborn child.

The state of Georgia should require drivers over the age of 75 to take a vision test and present a certificate of good health from a doctor before renewing their licenses.

Wyeth Daniels should be the next governor of the state.

Young people should monitor their blood pressure regularly to avoid health problems later in life.

As mentioned before, the proposition determines the approach to the speech, especially the organization. Also as mentioned earlier in this chapter, the exact phrasing of the proposition should be carefully done to be reasonable, positive, and appropriate for the context and audience. In the next section we will examine organizational factors for speeches with propositions of fact, value, and policy.

Organization Based on Type of Proposition

Organization for a proposition of fact.

If your proposition is one of fact, you will do best to use a topical organization. Essentially that means that you will have two to four discrete, separate arguments in support of the proposition. For example:

Proposition: Converting to solar energy can save homeowners money.

I. Solar energy can be economical to install.

A. The government awards grants. B. The government gives tax credits.

II. Solar energy reduces power bills.

III. Solar energy requires less money for maintenance.

IV. Solar energy works when the power grid goes down.

Here is a first draft of another outline for a proposition of fact:

Proposition: Experiments using animals are essential to the development of many life-saving medical procedures.

I. Research of the past shows many successes from animal experimentation.

II. Research on humans is limited for ethical and legal reasons.

III. Computer models for research have limitations.

However, these outlines are just preliminary drafts because preparing a speech of fact requires a great deal of research and understanding of the issues. A speech with a proposition of fact will almost always need an argument or section related to the “reservations,” refuting the arguments that the audience may be preparing in their minds, their mental dialogue. So the second example needs revision, such as:

I. The first argument in favor of animal experimentation is the record of successful discoveries from animal research.

II. A second reason to support animal experimentation is that re- search on humans is limited for ethical and legal reasons.

III. Animal experimentation is needed because computer models for research have limitations.

IV. Many people today have concerns about animal experimentation.

A. Some believe that all experimentation is equal.

1. There is experimentation for legitimate medical research. 2. There is experimentation for cosmetics or shampoos.

B. Others argue that the animals are mistreated.

- There are protocols for the treatment of animals in experimentation.

- Legitimate medical experimentation follows the protocols.

- Many of the groups that protest animal experimentation have extreme views.

- Some give untrue representations.

To complete this outline, along with introduction and conclusion, there would need to be quotations, statistics, and facts with sources provided to support both the pro-arguments in Main Points I-III and the refutation to the misconceptions about animal experimentation in Subpoints A-C under Point IV.

Organization for proposition of value

A persuasive speech that incorporates a proposition of value will have a slightly different structure. As mentioned earlier, a proposition of value must first define the “value” word for clarity and provide a basis for the other arguments of the speech. The second or middle section would present the defense or “pro” arguments for the proposition based on the definition. The third section would include refutation of the counter arguments or “reservations.” The following outline draft shows a student trying to structure a speech with a value proposition. Keep in mind it is abbreviated for illustrative purposes, and thus incomplete as an example of what you would submit to your instructor, who will expect more detailed outlines for your speeches.

Proposition: Hybrid cars are the best form of automotive transportation available today.

I. Automotive transportation that is best meets three standards. (Definition)

A. It is reliable and durable. B. It is fuel efficient and thus cost efficient. C. It is therefore environmentally responsible.

II. Studies show that hybrid cars are durable and reliable. (Pro-Ar- gument 1)

A. Hybrid cars have 99 problems per 100 cars versus 133 problem per 100 conventional cars, according to TrueDelta, a car analysis website much like Consumer Reports. B. J.D. Powers reports hybrids also experience 11 fewer engine and transmission issues than gas-powered vehicles, per 100 vehicles.

III. Hybrid cars are fuel-efficient. (Pro-Argument 2)

A. The Toyota Prius gets 48 mpg on the highway and 51 mpg in the city. B. The Ford Fusion hybrid gets 47 mpg in the city and in the country.

IV. Hybrid cars are environmentally responsible. (Pro-Argument 3)

A. They only emit 51.6 gallons of carbon dioxide every 100 miles. B. Conventional cars emit 74.9 gallons of carbon dioxide every 100 miles. C. The hybrid produces 69% of the harmful gas exhaust that a conventional car does.

V. Of course, hybrid cars are relatively new to the market and some have questions about them. (Reservations)

A. Don’t the batteries wear out and aren’t they expensive to replace?

Evidence to address this misconception.

Organization for a propositions of policy

The most common type of outline organizations for speeches with propositions of policy is problem-solution or problem-cause-solution. Typically we do not feel any motivation to change unless we are convinced that some harm, problem, need, or deficiency exists, and even more, that it affects us personally. As the saying goes, “If it ain’t broke, why fix it?”As mentioned before, some policy speeches look for passive agreement or acceptance of the proposition. Some instructors call this type of policy speech a “think” speech since the persuasion is just about changing the way your audience thinks about a policy.